Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Socialist Progressives

Related: About this forumLetís Not Forget Socialism in the Resurrection of Socialist Art

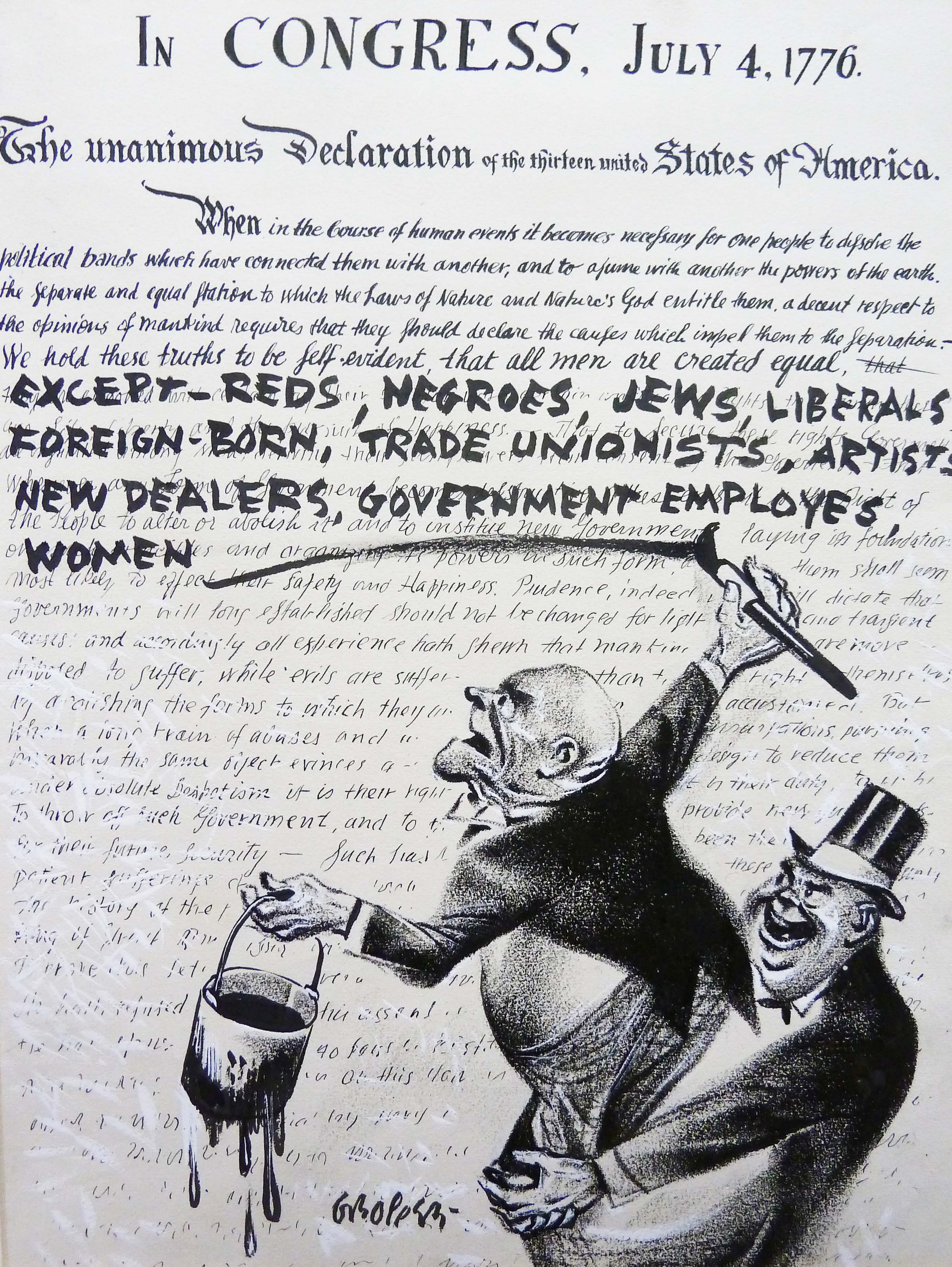

http://www.thenation.com/article/william-gropper-resurrection-of-socialist-art/Gropper was born to a pair of immigrant Jews on the Lower East Side in 1897. His father, Harry, had studied in several European universities and learned eight languages before immigrating to New York and finding little to do with his learning. He finally got work in a garment factory, where he met Jenny Nidel, also a new arrival. “The sweatshop gave us our livelihood but robbed us of our mother,” Gropper later recalled. (He once said that unlike Whistler, who famously depicted his mother as a solemn and dignified stoic, he would have painted his own as bending over a bathtub or a sewing machine.) Gropper spent his childhood getting pummeled by various gangs and drawing sidewalk pictures of cowboys and Indians that wrapped around the block. In 1911, a favorite aunt perished along with 145 other workers, most of them young Jewish women, in the devastating fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Greenwich Village. To say, as the museum does, that Gropper “was exposed to the rigors of the working class at a young age,” severely understates the point.

In 1915, Gropper was offered a scholarship to the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts by its founder (and now namesake), Frank Parsons. He began winning prizes for his work, including one for his cartoons, leading to his hiring by the New York Tribune as a sketch artist for feature stories. For the next several decades—in, as the museum tells us, “mainstream periodicals as well as more marginal publications,” including this one—Gropper “left a record of graphic comment on the twentieth century unique for its forceful presentation of ideas and lampooning of society’s ills,” as the late Joseph Anthony Gahn wrote in his 1966 dissertation, “The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist.” (Shamefully, Gahn’s work is the closest thing we have to a proper telling of Gropper’s life.)

One Depression-era poster by Gropper declares: against capitalist terror: against all forms of suppression of the political rights of workers. That now-neglected word, “suppression,” often appears in Gropper’s work, and as far as words go, it is, as the current leader of the Republican Party might say, one of the best. It appears again in a late 1930s drawing that, to my mind, offers a far more compelling visual metaphor for entwined grievances and social causes than the currently fashionable idea of “intersectionality.” Gropper’s drawing has a single tree with several of what the accompanying panel calls “negative influences” branching out from it: “war profits,” “race hatred,” intolerance, Charles Coughlin, “anti-labor propaganda,” the collusion of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Gropper called the drawing suppression. In his mind all of those scourges are connected at the roots. By contrast, intersectionality asks us to think of lines that meet only for a moment, before again going their separate ways.

The truly subversive idea—quite incompatible with Governor Cuomo’s thinking, as I understand it—that “race hatred” and “war profits” branch from the same rotten tree is not explored by the exhibit, which prefers to describe Gropper’s politics in terms more appropriate to today’s identity-based progressivism than to the socialism of the 1930s, when it would have been thought pathetically defensive to add the redundant modifier “democratic.” On this strained reading, Gropper was a proto-multiculturalist who “made great efforts to counter a general and widespread fear of anyone who was ‘different.’” He should interest us today not for his insistence on the kinship between capitalism and terror, but because he “focus[ed] on the diversity and strength of an American workforce that was coming together to create collective change.”

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

0 replies, 1458 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (8)

ReplyReply to this post