Louisiana

Related: About this forumOn Juneteenth, a look at the social, economic services done by Freedmen's Bureau agents in Louisiana

Juneteenth, the oldest known celebration marking the end of slavery in United States and a recognized holiday in 45 states, commemorates June 19, 1865, the day enslaved people in Texas finally received news of their freedom, more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation and two months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender. Including the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas declared free that day, roughly four million enslaved people across the country had been emancipated. To assist them in their transition into free society, President Abraham Lincoln established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in March 1865.

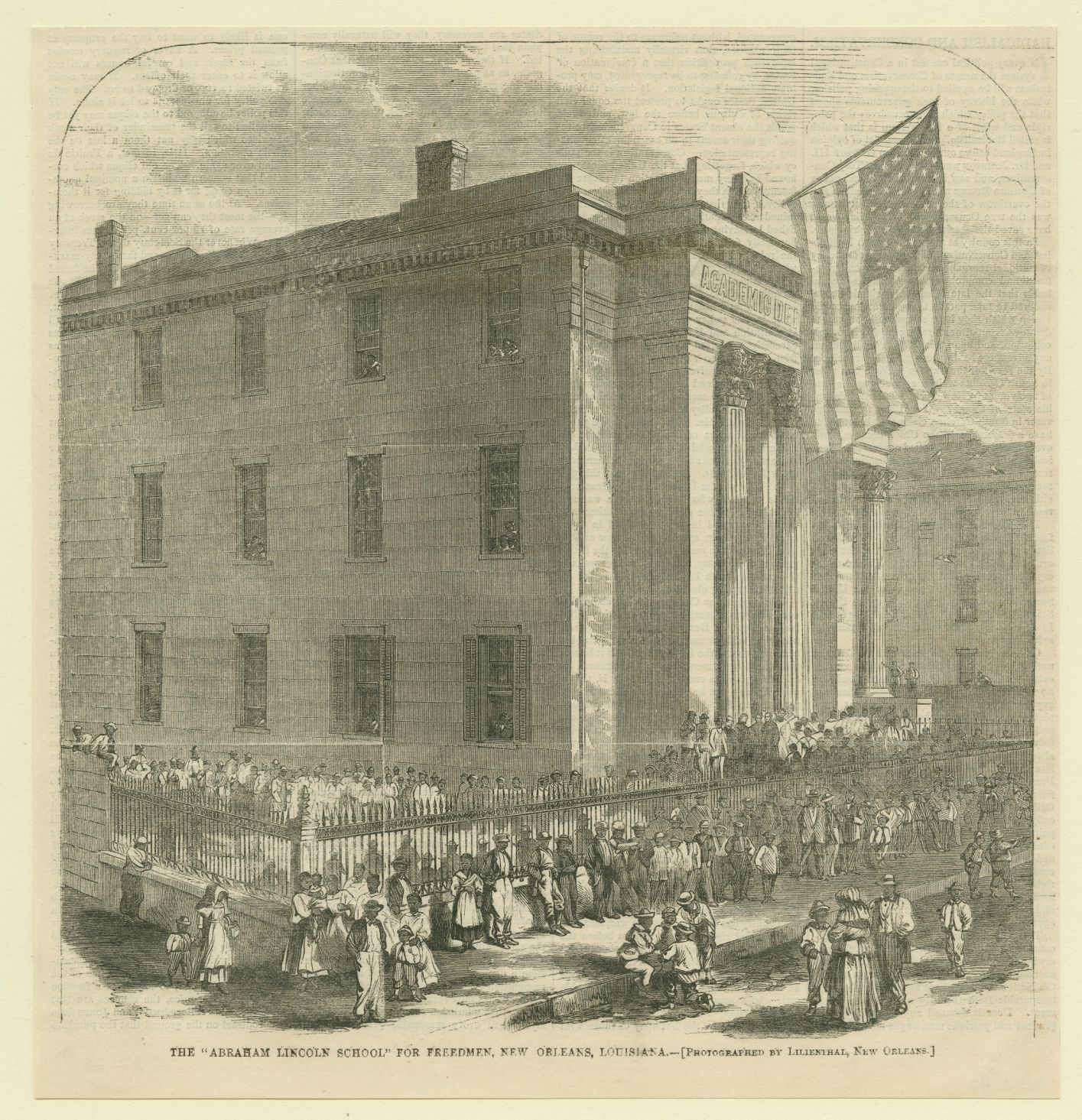

The Freedmen’s Bureau, as it’s more commonly known, provided social and economic services to formerly enslaved people and others living in poverty throughout the southern states and Washington, D.C. These services included assisting African American veterans in collecting pensions and back pay, distributing essential goods, facilitating labor contracts between sharecroppers and landowners, and helping to establish and maintain freedmen’s schools. Copies of Freedmen’s Bureau records in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s holdings contain a wealth of information about Bureau activities, especially education initiatives, in Louisiana during Reconstruction.

In the post-war South, the demand for education of newly freed people was enormous, and Freedmen’s Bureau agents were instrumental in establishing schools for African American children. Aaron Walker, one of these agents, wrote in an October 1865 report to the Bureau’s superintendent of education in Louisiana that he had helped to establish three schools in Shreveport and two in Natchitoches, each enrolling over 40 students. Walker commented that the number of potential students in Alexandria could fill at least two schools, but there was no building, or even room, in which to house the school. In Jefferson Parish, an agent (whose signature on the report is illegible) reported that his district contained 13 schools, but that he may have to close at least two due to insufficient funding.

This anecdote and others in the agents’ reports struck at one of the largest obstacles to creating and sustaining schools: money. The Bureau had originally instituted a plan where all Louisiana residents paid a five-percent tax to support these schools, but many whites protested, so a system in which only freedmen paid the tax replaced it. This tax created an extra burden on an already impoverished populace, agents observed. Walker reported that the Shreveport and Natchitoches school buildings were obtained with no rent required, but George Ruby, another agent, who went on to become a prominent African American political leader in Texas, wrote of a different situation in Amite Station in St. Helena Parish. “There are a large number of freedmen in the vicinity working the sawmills and elsewhere, who are all willing to sustain and anxious about their schools,” Ruby wrote, “but the trouble is just now their people though laboring, have little means.” The Jefferson Parish agent noted that he had “reasoned and explained to [the laborers] the great necesity (sic) of Education,” but that many objected to paying a tax that wasn’t being universally enforced.

Read more: http://www.theadvocate.com/new_orleans/entertainment_life/article_ba608ad6-7114-11e8-acb9-eb949222e4c2.html