Moche Octopus Headdress

by DR. MARY BROWN

Octopus Frontlet, Moche (La Mina), 300–600 C.E., gold, chrysocolla, shells, 27.9 × 43.1 × 4.4 cm, Peru (Museo de la Nación, Lima, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the brilliant light of what is now Peru, sunlight once poured over a golden supernatural being from the Moche culture (100–700 C.E.). When finished by a Moche artist, light would have reflected dramatically off the smooth surface of sheet gold cut and shaped into eight serrated appendages ending in animal faces. Identified as octopus tentacles, they emanate in bilateral symmetry from a central face with oversized fangs, staring frontal eyes, curling hair, and curving clawed feet flanked by small, wave-like spirals. The drama of the sun reflecting on the gold and the powerful symbolic imagery would have emanated power and prestige.

This headdress (c. 300–600 C.E.), recovered from a looted burial site in the Jequetepeque Valley along the northern coast of Peru, is considered one of the finest surviving examples of Moche metalwork for its superb craftsmanship and imagery that is emblematic of their deities and unique artistic style.

Moche sites (in what is today Peru) courtesy of the San José de Moro Archaeological Project

Octopus Frontlet, Moche (La Mina), 300–600 C.E., gold, chrysocolla, shells, 27.9 × 43.1 × 4.4 cm, Peru (Museo de la Nación, Lima, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The brilliance of Moche metalwork

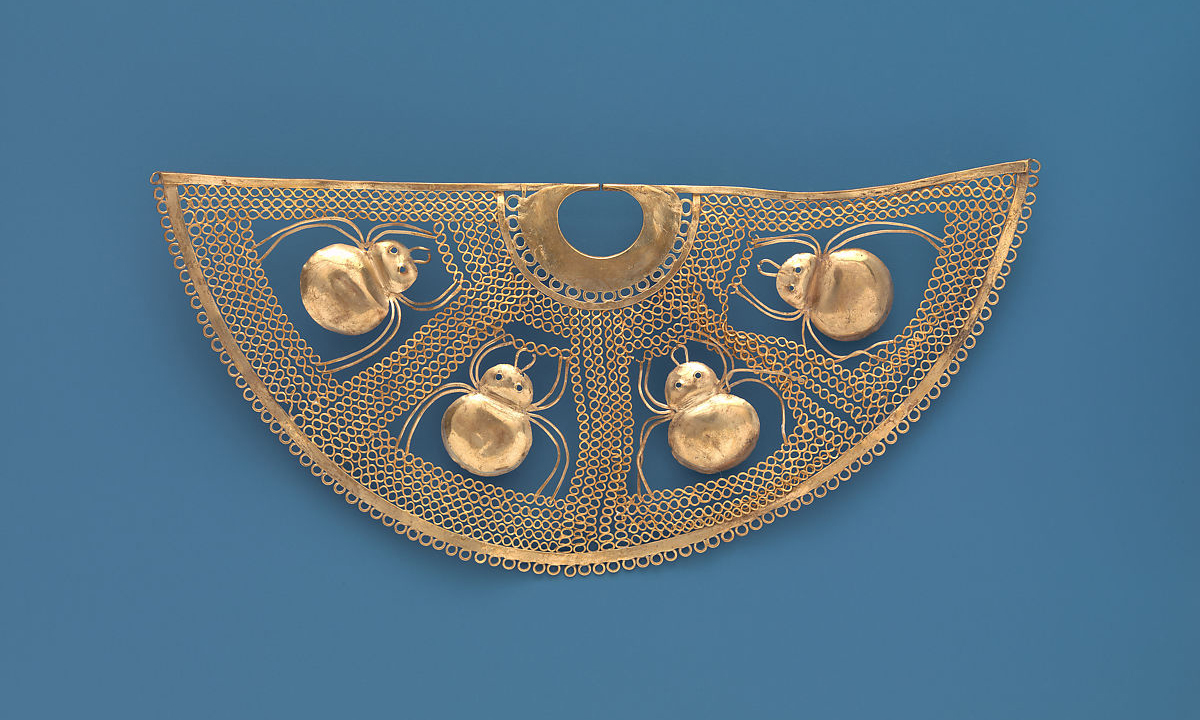

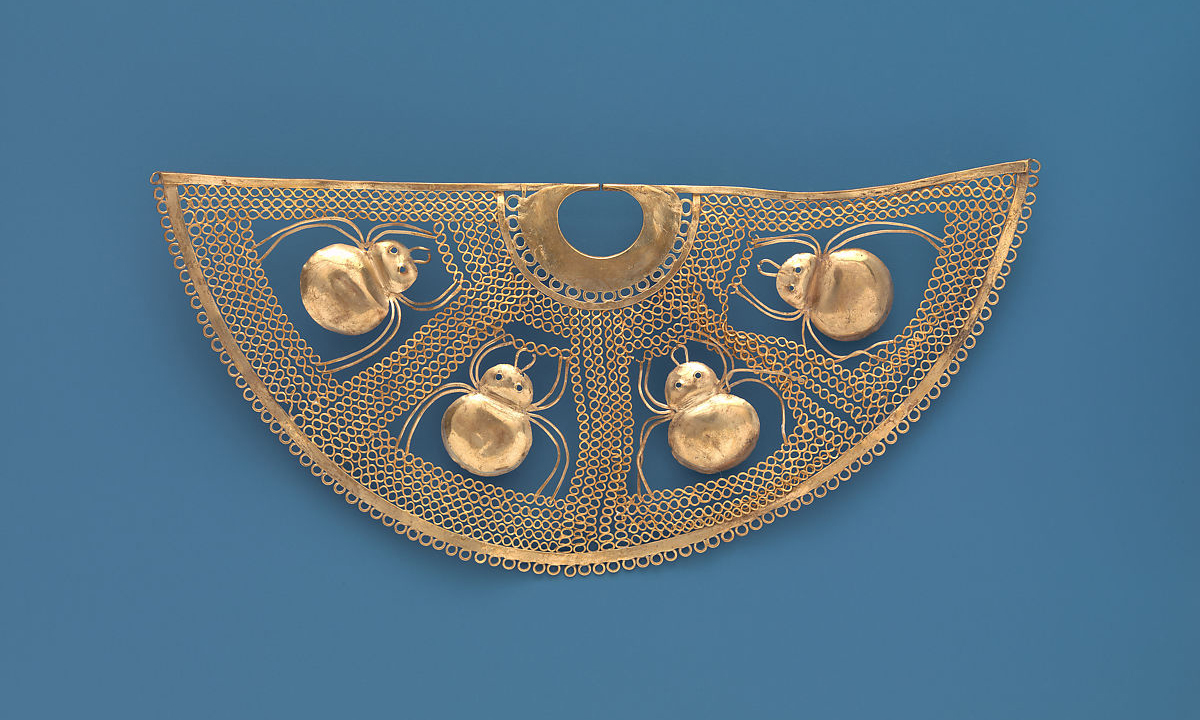

Salinar (?) culture, Nose Ornament with Spiders, 1st century B.C.E.–2nd century C.E., gold, Peru, North Coast, 5.1 x 11.1 x 0.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The headdress frontlet is part of the exceptional Moche metalwork tradition. Inheriting the skills developed by the earlier north coast Salinar culture, the Moche developed the most sophisticated metallurgy in the Andes. Some of their metalwork techniques were so advanced that they made gilded copper surfaces appear to be pure gold. [1] One of the most widely used artistic methods involved hammering metals into sheets, resulting in planar surfaces which could be cut and shaped into a range of forms that maximized the sun’s reflective effects. Sheet gold was also pressed over wooden or metal three-dimensional objects to create raised images, a technique called repoussé.

Nose Ornament with Intertwined Serpents, Moche, Peru, c. 390-450, gold, silver, shell, 12.5 x 21.1 x 1.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

These considerable skills were directed toward creating a rich array of personal adornment befitting a ruling class who, in part, consolidated and broadcast their power with regalia: headdresses, earspools, nose ornaments, beaded necklaces, pectorals, and even garments composed of individual metal pieces assembled with small wires. Some items included imagery as fine as spiders on delicately soldered webs. On the Octopus Headdress, small pieces dangling from the eyeshades would shimmer in the sun and further animate the face.

Octopus Frontlet, Moche (La Mina), 300–600 C.E., gold, chrysocolla, shells, 27.9 × 43.1 × 4.4 cm, Peru (Museo de la Nación, Lima, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

More:

https://smarthistory.org/moche-octopus-headdress/