50 years after Chile's dictatorship, human rights issues are still pending

Written by

Laura Chaparro Piedrahíta

Translated by

Melissa Vida

Read this post in Español

Translation posted 18 October 2023 3:45 GMT

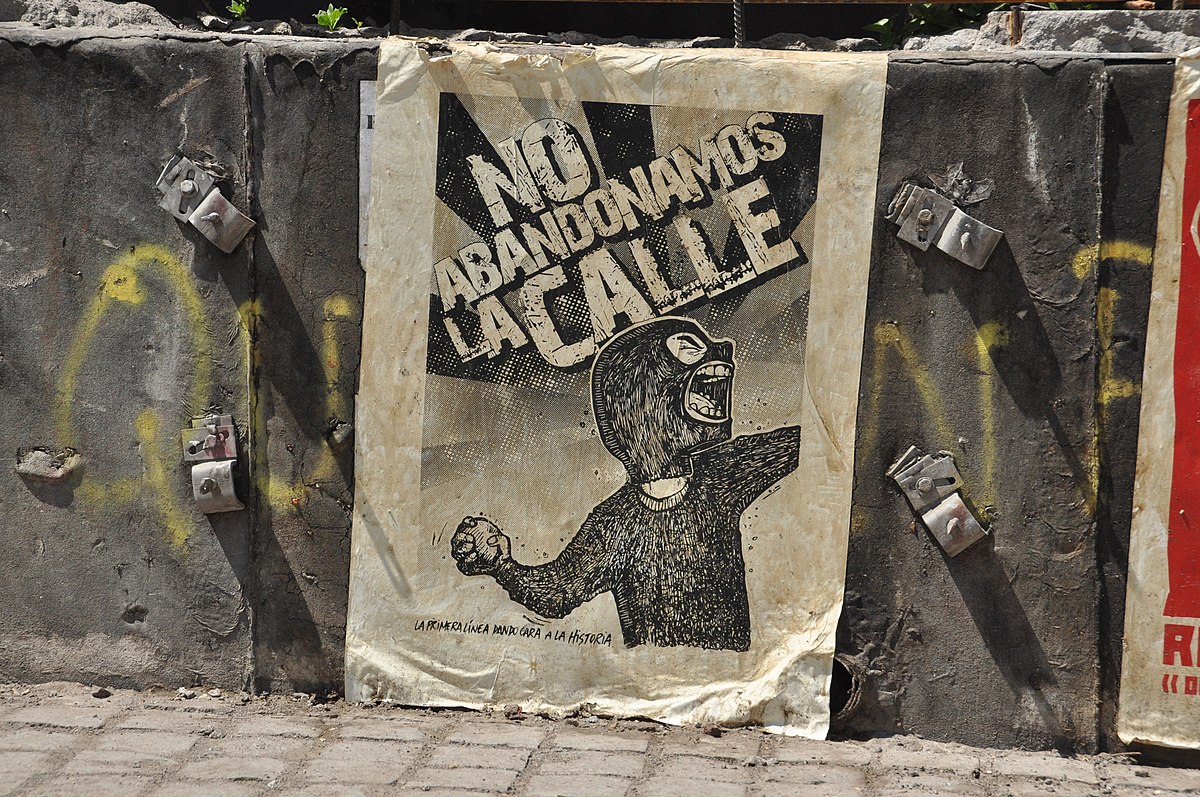

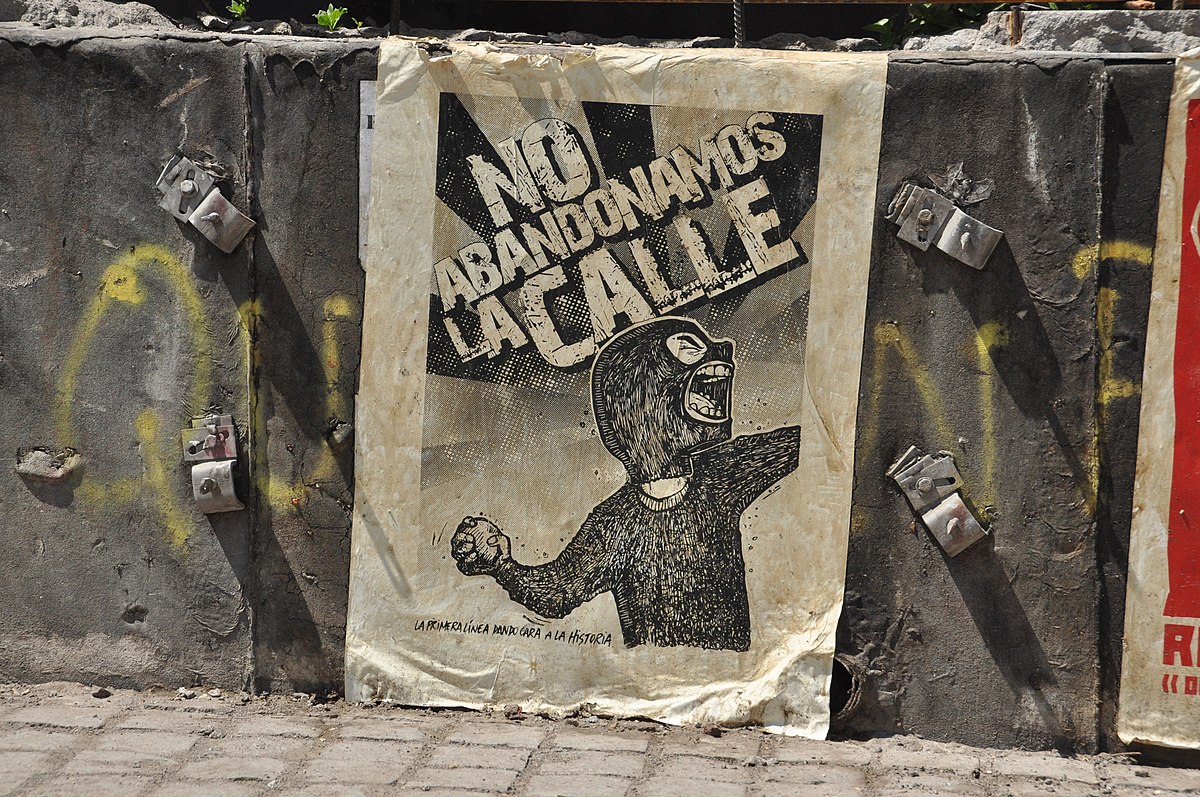

Street art in Santiago, Chile, created after the social uprising of October 2019. It reads “We will not give up on the streets (protests)”. Photo from Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED.

On September 11 this year, during the 50th anniversary of the coup d'état against socialist president Salvador Allende, thousands of Chileans marched to remember the more than 40,000 victims who were detained, disappeared, tortured, and executed during the 17 years of Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship. Pinochet implemented a repressive state policy, resorting to human rights violations through existing state bodies and others created solely for that purpose.

What started out as a peaceful protest culminated, however, in a series of clashes between demonstrators and the security forces in the capital Santiago. There, several individuals threw stones at the Palacio de la Moneda, the seat of the Chilean government, smashed the security barriers, and destroyed access to a cultural center located in the building. Tensions are evident in a country that many experts describe as fractured, divided, and polarized.

What happened during this commemoration inevitably mirrors another unfortunate episode in the country's history: the social uprising of 2019 that highlighted the deep socio-political problems that persist in Chile. On October 14, 2019, high school and university students gathered to dodge the Santiago subway fare as a protest against the increase in ticket prices in one of the countries with the highest cost of living in the region. But this was only the tip of the iceberg.

. . .

The 2019 social uprising was also marked by serious human rights violations against protesters, including authorities’ abuses against protesters, arbitrary arrests, and various cases of police violence including eye trauma and mutilations. As documented by Amnesty International, an estimated 8,000 people were victims of excessive use of state force.

One of the most emblematic cases is that of the now-senator Fabiola Campillai, a symbolic figure of the protests, who lost her eyesight and sense of smell due to the use of pellets by the carabineros. Although the perpetrator was convicted, as Lazo Jerez points out, “there are many other cases that remain unpunished.”

More:

https://globalvoices.org/2023/10/18/chiles-ongoing-debt-to-human-rights-victims/