Latin America

Related: About this forumMS-13 gangsters hunted by 'Black Shadow' death squad who 'hack off hands before killing'

MS-13 gangsters hunted by 'Black Shadow' death squad who 'hack off hands before killing'

The Authorities in El Salvador have cracked down hard on gangs, building brutal prisons where gang members have no hope of release – but the inmates are the lucky ones with death squads roaming the streets and torturing suspected gang members to death

By Michael Moran

Audience Writer

13:53, 25 MAR 2024

A former member of the MS-13 street gang says members live in constant fear of "death squads" hunted them down. Alex Sanchez became a member of the Mara Salvatrucha gang in the early 1980s, enduring the infamous savage beating that all new recruits have to undergo. He served time in a US prison and was deported back to El Salvador.

It was shortly after arriving in El Salvador that Alex was targeted by the Sombra Negra (or ‘Black Shadow’), one of the largest and most feared of the Salvadoran death squads.

He told the Insider podcast how, everywhere he went, he was ready for a shootout. He explained: “I had two people with me, two gang members that had been child soldiers in the in the [Salvadoran civil] war … I had two grenades and I gave them to the two guys, saying ‘I've never used a grenade, I’l probably blow myself up’.”

He claimed he was in much more danger at home than he had been on the streets of LA. Every day he was at risk of being shot or kidnapped and tortured.

Sombra Negra killers would patrol the streets in blacked-out vehicles and wear masks and costumes that disguised their identity. They would typically kidnap suspected gang members, tie them up and torture them for hours – hacking off hands and genitals or smashing their teeth with hammers.

More:

https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/world-news/ms-13-gangsters-hunted-black-32434994

RandySF

(70,619 posts)ret5hd

(21,320 posts)without reading more than what was posted above:

should we -support- a group that to me just sounds like a rival gang?

not being facetious…honest question.

Chainfire

(17,757 posts)Judi Lynn

(162,376 posts)America's Role in El Salvador's Deterioration

Many Salvadorans stayed in the U.S. after a devastating earthquake. But other disasters in the country were man-made.

By Raymond Bonner

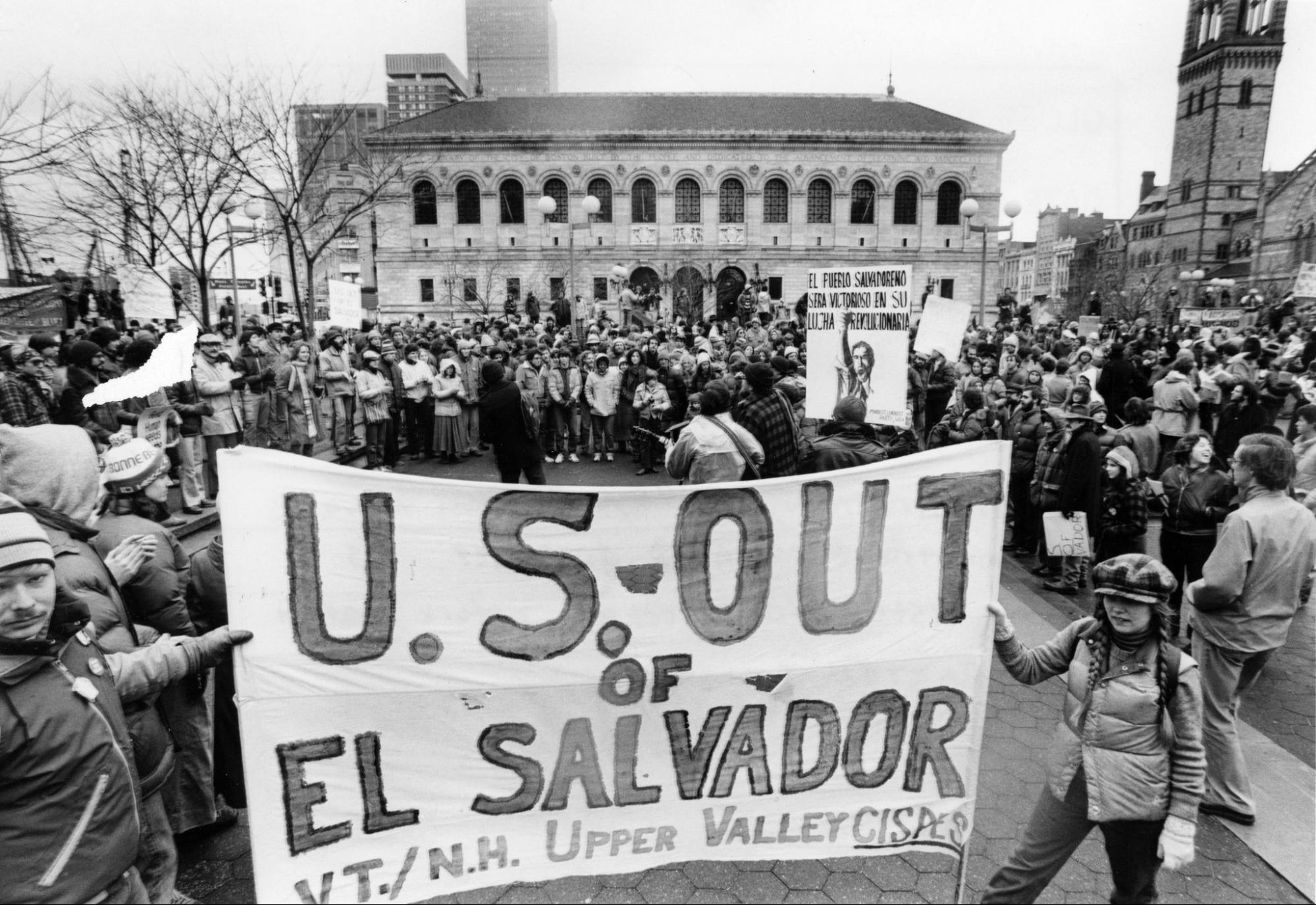

Anti-war marchers cross the Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C., on their way to the Pentagon for a rally to protest U.S. military involvement in El Salvador, on May 3, 1981. (Ira Schwarz / AP)

JANUARY 20, 2018

When Donald Trump said this month he would end temporary protected status for almost 200,000 Salvadorans, the number of immigrants standing to lose protections under this president approached the 1 million mark. This includes people, like those from El Salvador, that now stand to be deported to countries where their lives could be in danger. El Salvador has one of the world’s highest homicide rates—due in no small part to the policies of the country now trying to expel them.

Trump promised to end the protected status granted to Salvadorans in 2001 following a devastating earthquake. Then, a few days later, during a White House meeting on immigration policy, the president characterized places like El Salvador, along with Haiti, as “shithole” (or perhaps “shithouse”) countries. Unwilling to explicitly criticize the president for his intemperate remarks, Senator Marco Rubio expressed pity for the poor nation: “[T]he people of El Salvador and Haiti have suffered as the result of bad leaders, rampant crime and natural disasters.” Rubio omitted to note that one of the biggest disasters to befall El Salvador—one that created hundreds of thousands of refugees even before the post-earthquake wave—was man-made, with the United States, not nature, being a major force.

. . .

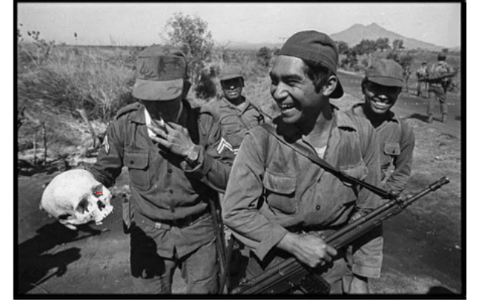

It was a civil war of the 1980s, one that pitted leftist revolutionaries against the alliance of countries, oligarchs, and generals that had ruled the country for decades—with U.S. support—keeping peasants illiterate and impoverished. It was a bloody, brutal, and dirty war.More than 75,000 Salvadorans were killed in the fighting, most of them victims of the military and its death squads. Peasants were shot en masse, often while trying to flee. Student and union leaders had their thumbs tied behind their backs before being shot in the head, their bodies left on roadsides as a warning to others.

. . .

Many Americans would prefer to forget that chapter in American history; those under the age of 40 may not even be aware of it. Salvadorans haven’t forgotten, however. In El Mozote and the surrounding villages of subsistence peasants, forensic experts are still digging up bodies—of women, children, and old men who were murdered by the Salvadoran army during an operation in December 1981. It was one of the worst massacres in Latin American history. But while Trump might smear the country’s image with crude language, today El Salvador has a functioning legal system—more than three decades after the event, 18 former military commanders, including a former minister of defense, are finally on trial for the El Mozote massacre.

Some 1,200 men, women and children were killed during the operation. Old men were tortured. Then executed. Mothers were separated from their children. Raped. Executed. Crying, frightened children were forced into the convent. Soldiers fired through the windows. More than a hundred children died; their average age was six.

“The United States was complicit,” Todd Greentree, who was a young political officer at the American embassy at the time, told me recently in an interview for a documentary about the massacre. Greentree noted that the massacre was carried out by the Atlacatl Battalion, which had just completed a three-month counterinsurgency training course in the United States. That training was also supposed to instill respect for human rights. The El Mozote operation was the battalion’s very first after completing the course.

When reports of the massacre first appeared in The New York Times and The Washington Post, the American ambassador, Deane Hinton, sent Greentree and a military attaché, Marine Corps Major John McKay, to investigate. They concluded there had been a massacre, and that the Atlacatl battalion was responsible, Greentree told me.

But that is not what Ambassador Hinton, a cigar-chomping career diplomat who died last year, reported to Washington. In an eight-page cable, he sought to lay the blame on the leftist guerillas. They had done “nothing to remove” the civilians “from the path of the battle which they were aware was coming,” he wrote. He then suggested that the victims may have been caught in a cross-fire, or as he put it, “could have been subject to injury as a result of the combat.” (Congress was also complicit because it continued to appropriate funds for El Salvador in spite of the military atrocities, says Greentree, who served in several diplomatic posts after El Salvador, including in Angola and Afghanistan, and has a doctorate in history from Oxford.)

The U.S.-fueled war drove tens of thousands of Salvadorans to flee the violence for safety in the United States. In the mid-90s, Clinton allowed their “temporary protected status” to expire. This decision contributed to the gang violence that marks El Salvador today—not long ago, when a day passed without a murder, it was banner news. Thousands of the refugees sent back were young men, who had either deserted from the army or the guerrillas during the war. And when they got back to El Salvador, with little beyond their fighting skills, they formed the nucleus of the gangs.

More:

https://web.archive.org/web/20240303160740/https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/trump-and-el-salvador/550955/

Judi Lynn

(162,376 posts)By Guy Gugliotta and Douglas Farah

March 21, 1993 at 12:00 a.m. EST

. . .

For 12 years, opponents of U.S. policy in Central America accused the Reagan and Bush administrations of ignoring widespread human rights abuses by the Salvadoran government and security forces and of systematically deceiving or even lying to Congress and the American people about the nature of an ally that would receive $6 billion in economic and military aid.

Their views appeared to be vindicated last week, when a three-man, U.N.-sponsored Truth Commission released a long-awaited report on 12 years of murder, torture and disappearance in El Salvador's civil war. The commission examined 22,000 complaints of atrocities and attributed 85 percent of a representative group of them to Salvadoran security forces or right-wing death squads. It blamed the remainder on the guerrilla Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN).

. . .

The Reagan administration is making no apologies. Elliott Abrams, who held two assistant secretaryships in the Reagan State Department, said "the administration's record in El Salvador is one of fabulous achievement," and attacks on it are "a post-Cold War effort to rewrite history." He dismissed Torricelli's threat as "McCarthyite crap."

Indeed, an examination of the public record fails to turn up statements that could be described as blatant lies. In speeches, interviews and countless appearances before Congress, a parade of Reagan and Bush officials vigorously defended U.S. policy in El Salvador, asserted that human rights was a top U.S. priority and insisted that the Salvadoran government's record was one of steady improvement.

. . .

But if there is no "smoking gun," there is overwhelming evidence, both in the officials' own documents and in their public statements, that if they did not know details about human rights abuses, it was because in many cases they chose not to know. The information was there.

. . .

And again, one year later, Ambassador Deane Hinton, in a speech before the American Chamber of Commerce in San Salvador, told his audience that "since 1979 perhaps as many as 30,000 Salvadorans have been murdered, not killed in battle, MURDERED {emphasis in the original}."

"Is it any wonder that much of the world is predisposed to believe the worst of a system which almost never brings to justice either those who perpetrate these acts or those who order them?" Hinton asked. The Reagan administration disavowed his remarks, saying the speech had not been cleared by the White House.

Critiques that came from outside the administration were most often ignored or dismissed as unwelcome: "The embassy never liked to hear the bad news," said Americas Watch counsel Jemera Rone, who worked in El Salvador in 1985-90. "So they attacked the messenger."

One reason so many people found it hard to believe that U.S. officials could not have known more about rights abuses and acted more aggressively to curb them is that the United States was deeply involved in running the war, from intelligence gathering to strategy planning to training of everyone from officers to foot soldiers.

senior U.S. official admitted he and others could have known much more than they did, but "these were the guys we were working with day in and day out, and we did not want to create a hostile situation." Besides, he said, "we were here to fight the guerrillas, they were the enemy, and we did not go around investigating our friends."

Sometimes officials painted the messenger as a communist dupe or even a sympathizer. In this way Abrams, as assistant secretary of state for human rights and humanitarian affairs, dismissed reports published in The Washington Post and the New York Times of massacres by Salvadoran army soldiers of hundreds of people in the village of El Mozote in December 1981.

More:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1993/03/21/12-years-of-tortured-truth-on-el-salvador/9432bb6f-fbd0-4b18-b254-29caa919dc98/

Judi Lynn

(162,376 posts)Death squads in El Salvador (Spanish: escuadrones de la muerte) were far-right paramilitary groups acting in opposition to Marxist–Leninist guerrilla forces, most notably of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), and their allies among the civilian population before, during, and after the Salvadoran Civil War. The death squads committed the vast majority of the murders and massacres during the civil war from 1979 to 1992 and were heavily aligned with the United States-backed government.[1][2][3]

According to the Attorney for the Defense of Human Rights (PDDH), death squads remain active in El Salvador. The PDDH registered 25 extrajudicial executions of gang members between May 2022 and May 2023 which it attributed to death squad activity during the country's gang crackdown.[4]

. . .

Post-civil war

During negotiations to end the civil war in what are now the Chapultepec Peace Accords, part of the agreements were that the government of El Salvador would crack down on and suppress the paramilitaries that fought alongside them during the civil war. The accords stated that the government would "[s]uppress paramilitary entities (Civil Defense Patrols)."[19]

Most of the paramilitaries that existed in the country before and during the civil war have since ceased to exist but one notable exception, Sombra Negra, continues to operate in the country, targeting gang members of MS-13 and 18th Street Gang as a form of vigilante justice.[20]

Human rights violations

During the civil war, the paramilitaries, often labeled as death squads, came to public attention when on March 24, 1980, Archbishop of San Salvador Óscar Romero was assassinated while giving Mass.[21] The Salvadoran government investigated but was unable to identify who assassinated Romero. The investigation did identify Major Roberto D'Aubuisson, a neo-fascist who commanded several death squads during the civil war,[22][23] as having ordered the assassination.[24][25]

The US-trained Atlácatl Battal

ion of the Salvadoran Army was responsible for committing two of the largest massacres during the civil war: the El Mozote massacre and the El Calabozo massacre.[26] Sombra Negra tortured victims, mostly gang members, and killed them with a point-blank shot to the head.[27][28]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_squads_in_El_Salvador#Bibliography

La Sombra Negra, El Salvador

Judi Lynn

(162,376 posts)US-funded police linked to illegal executions in El Salvador

Story by Nick Paton Walsh, Barbara Arvanitidis and Bryan Avelar

San Salvador, El Salvador (CNN) -- The United States has quietly funded and equipped elite paramilitary police officers in El Salvador who are accused of illegally executing gang members, CNN has learned.

Successive US administrations have pumped tens of millions of dollars into Salvadoran law enforcement and military to shore up the government’s “Mano Dura” or Firm Hand program, first launched in 2003 but redoubled in 2014 to tackle the country’s rampant gang problem.

Yet the country’s police will be broadly accused next month of “a pattern of behavior by security personnel amounting to extrajudicial executions” in a United Nations report, seen in advance by CNN, that will also call on Salvadoran security forces to break a “cycle of impunity” in which killings are rarely punished.

One police unit that killed 43 alleged gang members in the first six months of last year received significant US funding, CNN can reveal. Several of those deaths have been investigated as murders by Salvadoran police.

While the unit -- known as the Special Reaction Forces (FES) -- was disbanded earlier this year, many of its officers have joined a new elite force that currently receives US funding.

. . .

As FES officers were shooting gangsters dead in the streets, the US government was sending money and equipment to the group while also deporting thousands of MS-13 recruits back to El Salvador, further fueling the growth of the group in a country where police may be getting away with murder, according to the forthcoming UN report.

More:

https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2018/05/world/el-salvador-police-intl/