Latin America

Related: About this forumThe Pinochet Regime Declassified

DINA: “A Gestapo-Type Police Force” in Chile

Fifty Years after Official Creation, Declassified Documents Record Atrocities

Committed by Chilean Secret Security Force, DINA

Published: Jun 18, 2024

Briefing Book #

862

Edited by Peter Kornbluh and John Dinges

Washington, D.C., June 18, 2024 - On June 18, 1974, the official registry of the Chilean military dictatorship published Decree 521 on the “creation of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA),” the secret police force responsible for some of the regime’s most emblematic human rights crimes. To mark the 50th anniversary of DINA’s official creation, the National Security Archive today is publishing a curated collection of declassified CIA, DIA, FBI and State Department documents, along with key Chilean records, that reflect the history of DINA’s horrific human rights atrocities and terrorist crimes.

The decree signed by General Augusto Pinochet and other members of the military junta officially established DINA for “the purpose of producing intelligence collection requirements for the formulation of policies, plans and adoption of measures required for the security and development of the country,” but the measure also included three secret articles empowering DINA to operate as a secret police force to surveil, arrest, imprison and eliminate anyone considered an opponent of the regime. The new decree gave “legal/official blessing to an organization that is already fully active,” the U.S. Defense attaché reported to Washington. Other members of the Chilean military viewed the junta’s order as “the foundation upon which a Gestapo-type police force will be built.”

DINA was created as a military organization outside the military chain of command, instead reporting directly to Pinochet as chief of the junta. As the secret articles of the decree stated, the new Directorate of National Intelligence was the “continuation of the DINA Commission” established in November 1973, only eight weeks after the September 11, 1973, military coup. By the time it was officially inaugurated, DINA was already the most feared security force in Chile—if not all Latin America. “There are three sources of power in Chile,” one Chilean intelligence officer informed a U.S. military attaché in early 1974: “Pinochet, God and DINA.”

As the principal agency of the regime’s apparatus of repression, DINA became infamous for its secret torture centers, extrajudicial executions, the forced disappearances of hundreds of civilians and acts of international terrorism. The sinister secret police force, according to a special TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE Senate report based on still classified CIA documents, eventually grew to 3,800 officers, operatives and administrative personnel—the figure is mistyped in the report as 38,000—with an annual budget of $27 million. According to that study, DINA “was established as an arm of the presidency, under the direct control of President Pinochet.” DINA’s director, Col. Manuel Contreras, according to the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, “has reported exclusively to, and received orders only from President Pinochet.”

More:

https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/chile/2024-06-18/pinochet-regime-declassified

Judi Lynn

(162,948 posts)Confessing Evil:

A Performative Approach to Perpetrators= Confessions and Chilean Memory Politics

. . .

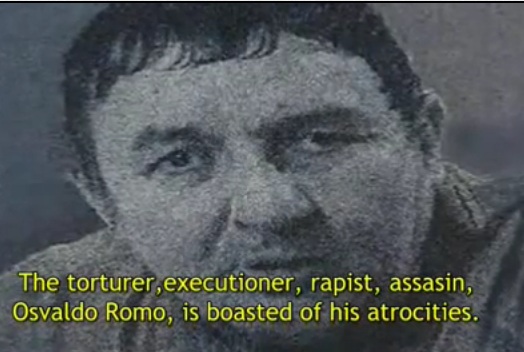

Osvaldo Romo Mena, alias Guatón (Big Fat) Romo, scandalized a Chilean and international

audience with this confession broadcast on the Miami-based cable television station Univisión in 1995.

Romo had served as a civilian member of DINA, General Augusto Pinochet=s secret police, during the

early years of the dictatorship (1973-75). He became well-known as one of the most brutal torturers

within the clandestine torture centers run by DINA.

Scholars have analyzed testimonials by victims of authoritarian state violence, but Romo=s

televised account reflects a new genre: authoritarian state perpetrators= confessions. The lack of

attention to perpetrators= confessions is not entirely surprising. Most perpetrators have remained silent

about their pasts. When they do confess, they tend to repeat the same denials used during the

authoritarian regimes. But increasingly in Latin America and in other parts of the world, perpetrators

have broken the code of silence and told their stories about authoritarian regime violence. Recognizing

the potential value that these confessions could have for Anunca más@ memory politics (or remembering

to not repeat the past), the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) institutionalized a

process by which perpetrators could receive amnesty in exchange for truthful confessions of political

crimes committed during the apartheid era. The TRC has become a model for future truth commissions

around the world, yet no systematic analysis to date explores the political impact of perpetrators=

confessions.2

Latin America, albeit without the unique amnesty arrangement offered in South Africa,

provides insights into the type of confessions that perpetrators make, how different social groups

respond to them, and the meaning of these confessions and the responses to them on political change

and stability.

How do Chileans react, for example, when Romo not only admits to using violence, but glorifies

it, and even appears to have derived pleasure from it? Romo=s account offers a unique study of

perpetrators= confessions. He, like most perpetrators, never apologizes for his past crimes. Indeed, he

does not recognize his acts as wrongdoing at all. His Aconfession@ therefore involves typical strategies

used by perpetrators to diffuse responsibility: remaining silent about some events, denying others,

justifying his acts as part of a Awar@ context, and Aforgetting@ details. What distinguishes Romo=s

confession from all others, however, is the perverse and sadistic pleasure he exudes, both through his

words and body, in harming others.

To analyze the impact of this, and other confessions, discursive analysis proves too limited.

2

What perpetrators say provides only part of the analysis. The unspoken cues that perpetrators use to

describe and explain themselves and their actions proves equally important in shaping political memory.

Moreover, where the confession is made shapes both what is said and how it is interpreted. The

political context in which the confession is made further influences the content of the text and responses

to it. How individuals and groups respond to the confession, moreover, influence its political impact.

Observers rarely passively watch perpetrators= confessions. Instead, they become active participants in

generating political meaning from them. This project, therefore, involves a performative analysis that

considers the interaction of timing, staging, acting, perpetrators= confessional scripts, and audience

responses to produce political meaning.

In particular, this project analyzes the impact of Romo=s confession on Anunca más@ memory

politics in Chile. It questions whether perpetrators= confessions alone B particularly the type made by

Romo B can have a positive impact on four components of that memory project: truth,

acknowledgment, justice, and collective memory. Certainly perpetrators= confessions have the potential

to provide new truths about the past. They could determine the location of the disappeared or explain

the cause of death. These confessions could, moreover, acknowledge, or confirm victims= accounts, by

accounting for the past violence and condemning it. Perpetrators= accounts could establish the facts

necessary to investigate, prosecute, and bring justice for past crimes. They could also advance

restorative and symbolic forms of justice through truth, acknowledgment, and acts of contrition. By

having perpetrators from within the repressive apparatus admit to its atrocities, confessions can advance

Acollective memory,@ or a common national understanding of human rights violations and a commitment

to avoid repeating them. How could anyone deny the violence of the past when those from within the

repressive apparatus admit to it?

On their own, perpetrators= confessions do not achieve these lofty goals. Sometimes they may

even work against them by hiding the truth, resurrecting the authoritarian regime=s denials and

justifications that blame, rather than acknowledge, victims for past violence, and escaping justice through

amnesty laws. Romo=s text represents one of those confessions that would have a negative impact on

memory politics. But by analyzing the interactions within the entire performance, this sadistic confession

provides a more realistic notion of how and when perpetrators confessions can positively influence

memory politics.

More:

http://lasa.international.pitt.edu/lasa2003/payneleigh.pdf

Osvaldo Romo

~ ~ ~

Wikipedia:

Human rights violations in Pinochet's Chile

Human rights violations in Pinochet's Chile were the crimes against humanity, persecution of opponents, political repression and state terrorism committed by the Chilean Armed Forces, members of Carabineros de Chile and civil repressive agents members of a secret police, during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile from September 11, 1973, until March 11, 1990.

According to the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation (Rettig Commission) and the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Valech Commission), the number of direct victims of human rights violations in Chile accounts for around 30,000 people: 27,255 tortured and 2,279 executed. In addition, some 200,000 people suffered exile and an unknown number went through clandestine centers and illegal detention.[citation needed]

The systematic human rights violations that were committed by the military government of Chile, under General Augusto Pinochet, included gruesome acts of physical and sexual abuse, as well as psychological damage. From 11 September 1973 to 11 March 1990, Chilean armed forces, the police and all those aligned with the military junta were involved in institutionalizing fear and terror in Chile.[1]

The most prevalent forms of state-sponsored torture that Chilean prisoners endured were electric shocks, waterboarding, beatings, and sexual abuse. Another common mechanism of torture employed was "disappearing" those who were deemed to be potentially subversive because they adhered to leftist political doctrines. The tactic of "disappearing" the enemies of the Pinochet regime was systematically carried out during the first four years of military rule. The "disappeared" were held in secret, subjected to torture and were often never seen again. Both the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Valech Report) and the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation (Rettig Report) approximate that there were around 30,000 victims of human rights abuses in Chile, with 27,255 tortured[2] and 2,279 executed.[3]

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_rights_violations_in_Pinochet%27s_Chile

https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BZWI3MjllN2EtMTFiNS00ODg4LTk5MmQtOTM1NGZjNTUyY2JjXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNjUxMjc1OTM@._V1_.jpg

Manuel Contreras

Manuel Contreras, at long last, on his way to the slammer for high-ranking fascist monsters

Judi Lynn

(162,948 posts)14 March, 2021 • Francisco Letelier

40 years after the assassination, artist Francisco Letelier paints a mural that goes on display at American University (photo courtesy American University Museum, Washington, DC).

The following essay derives from artist Francisco Letelier’s Paso del Condor Project, which examines the legacy of Operation Condor through text and art installations. Ironically, the project was partially funded by Michael Vernon Townley, the arch villain in this story—lawyers for the Soria lawsuit, mentioned below, have channeled some of the restitution payments Townley makes towards Letelier’s work. “I have been collecting information about Chile and the murders for over four decades now,” Letelier notes. “It is difficult to reach back that far.” —Ed.

Francisco Letelier

On September 21, 1976, I am pulled out of my home room at Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland, just outside of Washington DC. Our aunt Cecilia is waiting to drive my brother and me to George Washington Hospital. “There has been an accident” is all she will say. On the way we navigate snarled traffic, I hear the sound of sirens and emergency vehicles. We pass Sheridan Circle and the Chilean Embassy (Ambassador’s Residence), where firemen are hosing off the asphalt. At the hospital we learn that a car bomb has ended the life of my father, Orlando Letelier, and the life of Ronni Karpen Moffitt, a 23-year-old colleague.

The day after the murders, we are all in shock, barely able to talk, weighed down by a crushing darkness. The FBI wants to question us and one by one we are escorted over to the house next door. Our neighbor on a quiet cul de sac happens to be an FBI agent, and the interrogations are held in his living room.

I was sleeping in my bedroom with an open window, when yards away, Michael Townley, who will soon become famous as an assassin, crawls under the light blue Malibu sedan parked in our driveway and secures the bomb.

The agent and his co-conspirators hide in plain sight, sitting in a car on the street casing our home, noting the comings and goings of family members. I borrow the car when I can wrestle it away from my parents and drive it with the C2 explosive attached to its undercarriage in the days before it is detonated.

The 1976 assassination of former Chilean ambassador and dissident Orlando Letelier along Embassy Row shocked the nation (photo Washington Post).

The bomb severs my father’s legs. As he bleeds to death, Ronni makes it out of the car to the sidewalk, but soon drowns in her own blood from a piece of shrapnel in her throat. They set up the questioning in my neighbor’s living room. I can hear the metallic swish of the basketball hoop set at the end of the cul de sac. When I’m called over, the men know a lot about my father, his travels and friendships.

More:

https://themarkaz.org/dinner-at-the-white-house-in-the-lions-den/

~ ~ ~

Wikipedia:

. . .

Background

In 1971, Letelier was appointed ambassador to the United States by Salvador Allende, the socialist president of Chile.[3] Letelier had lived in Washington, D.C., during the 1960s and had supported Allende's campaign for the presidency. Allende believed Letelier's experience and connections in international banking would be highly beneficial to developing US–Chile diplomatic relations.[4] During 1973, Letelier served successively as Minister of Foreign Affairs, then Interior Minister, and, finally, Defense Minister. After the Chilean coup of 1973 that brought Augusto Pinochet to power, Letelier was one of the first members of the Allende administration to be arrested by the Chilean government and sent to a political prison in Tierra del Fuego.

He was held for 12 months in different concentration camps and suffered severe torture: first at the Tacna Regiment, then at the Military Academy. Later, he was sent to a political prison for eight months at Dawson Island. From there, he was transferred to the basement of the Air Force War Academy, and finally to the concentration camp of Ritoque. Eventually, international diplomatic pressure, especially from Diego Arria, then Governor of the Federal District of Venezuela, and United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger[5] resulted in Letelier's sudden release on the condition that he immediately leave Chile for Venezuela. He was told by the officer in charge of his release that "the arm of DINA is long; General Pinochet will not and does not tolerate activities against his government." This was a clear warning to Letelier that living outside of Chile would not guarantee his safety.[6]

After his release in 1974, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he became a senior fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies, an independent international policy studies think tank.[7] He plunged into writing, speaking and lobbying the US Congress and European governments against Augusto Pinochet's regime, and soon he became the leading voice of the Chilean resistance, in the process preventing several loans (especially from Europe) from being awarded to the military government. He was described by his colleagues as being "the most respected and effective spokesman in the international campaign to condemn and isolate" Pinochet's government.[8] Letelier was assisted at the Institute for Policy Studies by Ronni Moffitt, a 25-year-old fundraiser who ran a "Music Carryout" program that produced musical instruments for the poor, and also campaigned for democracy in Chile.[9]

. . .

Assassination

Orlando Letelier was driving to work in Washington, D.C., on 21 September 1976, with Ronni Moffitt (January 10, 1951 – September 21, 1976) and her husband of four months, Michael. Letelier was driving, while Moffitt was in the front passenger seat, and Michael was in the back behind his wife.[16] As they rounded Sheridan Circle in Embassy Row at 9:35 am EDT, an explosion erupted under the car, lifting it off the ground. When the car came to a halt after colliding with a Volkswagen illegally parked in front of the Irish Embassy, Michael was able to escape from the rear end of the car by crawling out of the back window. He then saw his wife stumbling away from the car and, assuming that she was safe, went to assist Letelier, who was still in the driver seat,[17] barely conscious and appearing to be in great pain. Letelier's head was rolling back and forth, his eyes moved slightly, and he muttered unintelligibly.[citation needed] Michael tried to remove Letelier from the car, but was unable to do so, despite the fact that much of Letelier's lower torso was blown away and his legs had been severed.[18]

Both Ronni Moffitt and Orlando Letelier were taken to the George Washington University Medical Center shortly thereafter. At the hospital, it was discovered that Ronni's larynx and carotid artery had been severed by a piece of flying shrapnel.[18] She drowned in her own blood some 30 minutes after Letelier's death,[17] while Michael suffered only a minor head wound. Michael estimated the bomb was detonated at approximately 9:30 am; the medical examiner report set the time of Letelier's death at 9:50 am and Moffitt's at 10:37 am, the cause of death for both listed as explosion-incurred injuries due to a car bomb placed under the car on the driver's side.[citation needed]

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assassination_of_Orlando_Letelier#:~:text=Orlando%20Letelier%20was%20driving%20to,the%20back%20behind%20his%20wife.

Judi Lynn

(162,948 posts)Michael V. Townley

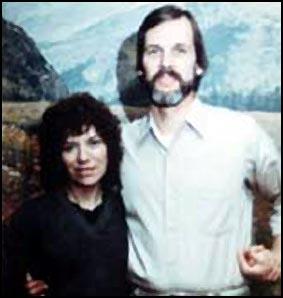

Michael Vernon Townley was born in Waterloo, Iowa, in 1942. His father, Vernon Townley, was appointed head of the Ford Motor Company in Chile. As a result, the family moved to Santiago. Vernon Townley, who had developed links with the CIA while working in the Philippines, became involved in politics and helped fund the 1958 presidential campaign of conservative candidate, Jorge Alessandri who narrowly managed to defeat Salvador Allende in the election.

Michael Townley went to work for Investors Overseas Services, the company owned by Bernard Cornfeld and Robert Vesco. In 1961 Townley married Mariana Callejas. Although active in the Socialist Party of Chile, she was actually working as an informer for Chilean military intelligence. Soon afterwards Townley began working for the CIA. He became associated with a Cuban group called the Chicago Junta. This group included Frank Sturgis, Orlando Bosch, Antonio Veciana and Aldo Vera Serafin. According to Peter Dale Scott, this operational hit team was disbanded on 21st November, 1963, the day before John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

In 1967 Townley moved to Miami. According to Donald Freed (Death in Washington: The Murder of Orlando Letelier) Towney was now being sponsored by Frank Sturgis and the Secret Army Organization (SAO). "Townley began an intensive study of electronics and explosives under the tutelage of several former CIA men who were in the process of taking over an electronics operation in the Fort Lauderdale area." One of Townley's tasks was to plant bombs under the cars of people living in Miami.

Mariana Callejas and Michael Townley

In 1969 the CIA arranged for Townley to be sent to Chile under the alias of Kenneth W. Enyart. He was accompanied by Aldo Vera Serafin of the SAO. Townley now came under the control of David Atlee Phillips who had been asked to lead a special task force assigned to prevent the election of Salvador Allende as President of Chile. This campaign was unsuccessful and Allende gained power in 1970. He therefore became the first Marxist to gain power in a free democratic election.

More:

https://spartacus-educational.com/JFKtownleyM.htm