Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

American History

Related: About this forumOn this day, March 12, 1928, the St. Francis Dam in Los Angeles failed.

St. Francis Dam

Tools

Coordinates: 34°32'49"N 118°30'45"W

View of the dam looking north, with water in its reservoir, in February 1927

Location: Los Angeles County, California, U.S.

Coordinates: 34°32'49"N 118°30'45"W

Construction began: 1924; 100 years ago

Opening date: 1926; 98 years ago

Demolition date: 1929; 95 years ago

Dam and spillways

Impounds: Los Angeles Aqueduct; San Francisquito Creek

Height: 185 ft (56 m)

Height (foundation): 205 ft (62 m)

Length: main dam 700 ft (210 m); wing dike 588 ft (179 m)

Elevation at crest parapet: 1,838 ft (560 m); spillway 1,835 ft (559 m)

Width (crest): 16 ft (4.9 m)

Width (base): 170 ft (52 m)

Parapet width: 16 ft (4.9 m)

Hydraulic head: 182 ft (55 m)

Dam volume: main dam 130,446 cu yd (99,733 m3); wing dike 3,826 cu yd (2,925 m3)

The St. Francis Dam, or the San Francisquito Dam, was a concrete gravity dam located in San Francisquito Canyon in northern Los Angeles County, California, United States, that was built between 1924 and 1926. The dam failed catastrophically in 1928, killing at least 431 people in the subsequent flood, in what is considered to have been one of the worst American civil engineering disasters of the 20th century and the third-greatest loss of life in California history.

The dam was built to serve the growing water needs of the city of Los Angeles, creating a large regulating and storage reservoir that was an integral part of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. It was located in San Francisquito Canyon of the Sierra Pelona Mountains, about 40 miles (64 km) northwest of downtown Los Angeles, and approximately 10 miles (16 km) north of the present day city of Santa Clarita.

However, a defective soil foundation and design flaws led to the dam's collapse just two years after its completion. Its failure ended the career of William Mulholland, the general manager and chief engineer of the Bureau of Water Works and Supply (now the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).

Background

A cross section view of the St Francis Dam after collapse

Another view of the St Francis Dam after collapse

{snip}

Dam instability

Water began to fill the reservoir on March 12, 1926. It rose steadily and rather uneventfully, although several temperature and contraction cracks did appear in the dam, and a minor amount of seepage began to flow from under the abutments. In accord with the protocol for design, which had been established by the Engineering department during construction of the Mulholland Dam, no contraction joints were incorporated. The most notable incidents were two vertical cracks that ran down through the dam from the top; one was approximately 58 feet (18 m) west of the outlet gates and another about the same distance to the east. Mulholland, along with his Assistant Chief Engineer and General Manager Harvey Van Norman, inspected the cracks and judged them to be within expectation for a concrete dam the size of the St. Francis.

At the beginning of April, the water level reached the area of the inactive San Francisquito Fault line in the western abutment. Some seepage began almost immediately as the water covered this area. Workers were ordered to seal off the leak, but they were not entirely successful, and water continued to permeate through the face of the dam. A two-inch pipe was used to collect this seepage and was laid from the fault line down to the home of the dam keeper, Tony Harnischfeger, which he used for domestic purposes. Water that collected in the drainage pipes under the dam to relieve the hydrostatic uplift pressure was carried off in this manner as well.

In April 1927 the reservoir level was brought to within 10 feet (3.0 m) of the spillway, and during most of May the water level was within 3 feet (0.91 m) of overflowing. There were no large changes in the amount of the seepage that was collected and, month after month, the pipe flowed about one-third full. This was an insignificant amount for a dam the size of the St. Francis, and on this subject Mulholland said, "Of all the dams I have built and of all the dams I have ever seen, it was the driest dam of its size I ever saw." The seepage data recorded during the 1926–1927 period shows that the dam was an exceptionally dry structure.

{snip}

On March 7, 1928, the reservoir was three inches below the spillway crest and Mulholland ordered that no more water be turned into the St. Francis Dam. Five days later, while conducting his morning rounds, Harnischfeger discovered a new leak in the west abutment. Concerned not only because other leaks had appeared in this same area in the past but more so that the muddy color of the runoff he observed could indicate the water was eroding the foundation of the dam, he immediately alerted Mulholland. After arriving, both Mulholland and Van Norman began inspecting the area of the leak. Van Norman found the source and by following the runoff, determined that the muddy appearance of the water was not from the leak itself but came from where the water contacted loose soil from a newly cut access road. The leak was discharging 2 to 3 cubic feet (15 to 22 US gal; 57 to 85 L) per second of water by their approximation. Mulholland and Van Norman's concern was heightened not only by the leak's location but by the inconsistent volume of the discharge, according to their testimony at the coroner's inquest. On two occasions as they watched, an acceleration or surging of the flow was noticed by both men. Mulholland felt that some corrective measures were needed, although this could be done at some time in the future.

For the next two hours Mulholland, Van Norman and Harnischfeger inspected the dam and various leaks and seepages, finding nothing out of the ordinary or of concern for a large dam. With both Mulholland and Van Norman convinced that the new leak was not dangerous and that the dam was safe, they returned to Los Angeles.

Collapse and flood wave

St. Francis Dam in February 1927

Two and a half minutes before midnight on March 12, 1928, the St. Francis Dam catastrophically failed.

There were no surviving eyewitnesses to the collapse, but at least five people passed the dam less than an hour before without noticing anything unusual. The last, Ace Hopewell, a carpenter at Powerhouse No. 1, rode his motorcycle past the dam about ten minutes before midnight. At the coroner's inquest, Hopewell testified he had passed Powerhouse No. 2 without seeing anything there or at the dam that caused him concern. He stated at approximately one and one-half miles (2.4 km) upstream he heard, above his motorcycle's engine noise, a rumbling much like the sound of "rocks rolling on the hill." Hopewell stopped, got off his motorcycle and smoked a cigarette while checking the hillsides. The rumbling had begun to fade, and Hopewell assumed the sound was a landslide common to the area. Hopewell finished his cigarette, got back on his motorcycle and left. He was the last person to see the St. Francis Dam intact and survive.

At both of the Bureau of Power and Light's receiving stations in Los Angeles and at the Bureau of Water Works and Supply at Powerhouse No. 1, there was a sharp voltage drop at 11:57:30 p.m. Simultaneously, a transformer at Southern California Edison's (SCE) Saugus substation exploded, a situation investigators later determined was caused by wires up the western hillside of San Francisquito Canyon about ninety feet above the dam's east abutment shorting.

The same view of the "Tombstone" post-collapse. The west (left) abutment was entirely swept away. The inactive San Francisquito Fault is clearly visible, being located along the contact zone of schist and conglomerate.

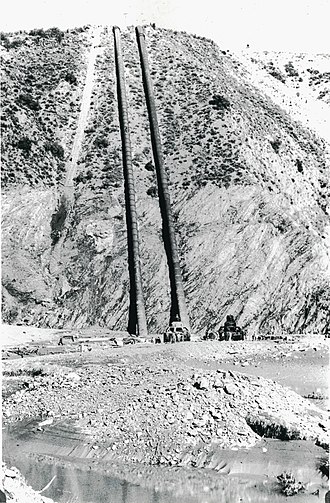

Power Plant 2 before dam collapse

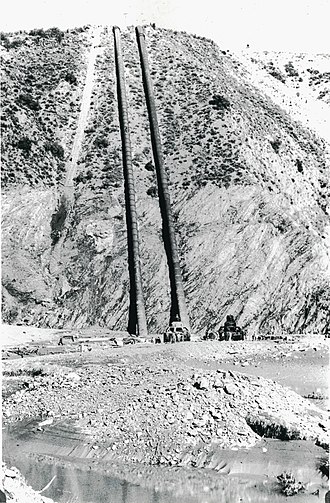

Power Plant 2 after dam collapse

Given the known height of the flood wave, and the fact that within seventy minutes or less after the collapse the reservoir was virtually empty, the failure must have been sudden and complete. Seconds after it began, little of the dam remained standing, other than the center section and wing wall. The main dam, from west of the center section to the wing wall abutment atop the hillside, broke into several large pieces and numerous smaller pieces. All of these were washed downstream as 12.4 billion gallons (47 million m³) of water began surging down San Francisquito Canyon. The largest piece, weighing approximately 10,000 tons (9,000 metric tons) was found about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) below the dam site.

Somewhat similarly, the dam portion east of the center section had also broken into several larger and smaller pieces. Unlike the western side, most of these came to rest near the base of the standing section. The largest fragments fell across the lower portion of the standing section, coming to rest partially on its upstream face. Initially, the two remaining sections of the dam remained upright. As the reservoir lowered, water undercut the already undermined eastern portion, which twisted and fell backwards toward the eastern hillside, breaking into three sections.

Harnischfeger and his family were most likely among the first casualties caught in the initially 140 feet (43 m) high flood wave, which swept over their cottage about a one-quarter mile (400 m) downstream from the dam. The body of a woman who lived with the family was found fully clothed and wedged between two blocks of concrete near the base of the dam. This led to the suggestion she and Harnischfeger may have been inspecting the structure immediately before its failure. Neither the bodies of Harnischfeger nor his six-year-old son were found.

Five minutes after the collapse, the then 120-foot-high (37 m) flood wave had traveled one and one-half miles (2.4 km) at an average speed of 18 miles per hour (29 km/h), destroying Powerhouse No. 2 and taking the lives of 64 of the 67 workmen and their families who lived nearby. This cut power to much of Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. Power was quickly restored via tie-lines with SCE, but as the floodwater entered the Santa Clara riverbed it overflowed the river's banks, flooding parts of present-day Valencia and Newhall. At about 12:40 a.m. SCE's two main lines into the city were destroyed by the flooding, re-darkening the areas that had earlier lost power and spreading the outage to other areas served by SCE. Nonetheless, power to most of the areas not flooded was restored with power from SCE's Long Beach steam electric generating plant.

Near 1:00 a.m. the mass of water, then 55 ft (17 m) high,[54] followed the river bed west and demolished SCE's Saugus substation, cutting power to the entire Santa Clara River Valley and parts of Ventura and Oxnard. At least four miles of the state's main north–south highway was under water and the town of Castaic Junction was being washed away.

The flood entered the Santa Clarita River Valley at 12 mph (19 km/h). Approximately five miles downstream, near the Ventura–Los Angeles county line, a temporary construction camp SCE had set up for its 150-man crew on the flats of the riverbank was hit. In the confusion, SCE personnel had been unable to issue a warning and 84 workers perished. Shortly before 1:30 a.m., a Santa Clara River Valley telephone operator learned from the Pacific Long Distance Telephone Company that the St. Francis Dam had failed. She called a motorcycle officer with the State Motor Division, then began calling the homes of those in danger. The officer went door-to-door warning residents about the imminent flood. At the same time, a deputy sheriff drove up the valley, toward the flood, with his siren blaring, until he had to stop at Fillmore.

The flood heavily damaged the towns of Fillmore, Bardsdale and Santa Paula before emptying both victims and debris into the Pacific Ocean 54 miles (87 km) downstream south of Ventura, at what is now the West Montalvo Oil Field, around 5:30 a.m., at which point the wave was almost two miles (3 km) wide and still traveling at 6 mph (9.7 km/h).

Newspapers across the country carried accounts of the disaster. The front page of the Los Angeles Times ran four stories, including aerial photos of the collapsed dam and the ruins of Santa Paula. In a statement, Mulholland said, "I would not venture at this time to express a positive opinion as to the cause of the St. Francis Dam disaster... Mr. Van Norman and I arrived at the scene of the break around 2:30 a.m. this morning. We saw at once that the dam was completely out and that the torrential flood of water from the reservoir had left an appalling record of death and destruction in the valley below." Mulholland stated that it appeared that there had been major movement in the hills forming the western buttress of the dam, adding that three eminent geologists, Robert T. Hill, C. F. Tolman and D.W. Murphy, had been hired by the Board of Water and Power Commissioners to determine if this was the cause.

{snip}

Tools

Coordinates: 34°32'49"N 118°30'45"W

View of the dam looking north, with water in its reservoir, in February 1927

Location: Los Angeles County, California, U.S.

Coordinates: 34°32'49"N 118°30'45"W

Construction began: 1924; 100 years ago

Opening date: 1926; 98 years ago

Demolition date: 1929; 95 years ago

Dam and spillways

Impounds: Los Angeles Aqueduct; San Francisquito Creek

Height: 185 ft (56 m)

Height (foundation): 205 ft (62 m)

Length: main dam 700 ft (210 m); wing dike 588 ft (179 m)

Elevation at crest parapet: 1,838 ft (560 m); spillway 1,835 ft (559 m)

Width (crest): 16 ft (4.9 m)

Width (base): 170 ft (52 m)

Parapet width: 16 ft (4.9 m)

Hydraulic head: 182 ft (55 m)

Dam volume: main dam 130,446 cu yd (99,733 m3); wing dike 3,826 cu yd (2,925 m3)

The St. Francis Dam, or the San Francisquito Dam, was a concrete gravity dam located in San Francisquito Canyon in northern Los Angeles County, California, United States, that was built between 1924 and 1926. The dam failed catastrophically in 1928, killing at least 431 people in the subsequent flood, in what is considered to have been one of the worst American civil engineering disasters of the 20th century and the third-greatest loss of life in California history.

The dam was built to serve the growing water needs of the city of Los Angeles, creating a large regulating and storage reservoir that was an integral part of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. It was located in San Francisquito Canyon of the Sierra Pelona Mountains, about 40 miles (64 km) northwest of downtown Los Angeles, and approximately 10 miles (16 km) north of the present day city of Santa Clarita.

However, a defective soil foundation and design flaws led to the dam's collapse just two years after its completion. Its failure ended the career of William Mulholland, the general manager and chief engineer of the Bureau of Water Works and Supply (now the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).

Background

A cross section view of the St Francis Dam after collapse

Another view of the St Francis Dam after collapse

{snip}

Dam instability

Water began to fill the reservoir on March 12, 1926. It rose steadily and rather uneventfully, although several temperature and contraction cracks did appear in the dam, and a minor amount of seepage began to flow from under the abutments. In accord with the protocol for design, which had been established by the Engineering department during construction of the Mulholland Dam, no contraction joints were incorporated. The most notable incidents were two vertical cracks that ran down through the dam from the top; one was approximately 58 feet (18 m) west of the outlet gates and another about the same distance to the east. Mulholland, along with his Assistant Chief Engineer and General Manager Harvey Van Norman, inspected the cracks and judged them to be within expectation for a concrete dam the size of the St. Francis.

At the beginning of April, the water level reached the area of the inactive San Francisquito Fault line in the western abutment. Some seepage began almost immediately as the water covered this area. Workers were ordered to seal off the leak, but they were not entirely successful, and water continued to permeate through the face of the dam. A two-inch pipe was used to collect this seepage and was laid from the fault line down to the home of the dam keeper, Tony Harnischfeger, which he used for domestic purposes. Water that collected in the drainage pipes under the dam to relieve the hydrostatic uplift pressure was carried off in this manner as well.

In April 1927 the reservoir level was brought to within 10 feet (3.0 m) of the spillway, and during most of May the water level was within 3 feet (0.91 m) of overflowing. There were no large changes in the amount of the seepage that was collected and, month after month, the pipe flowed about one-third full. This was an insignificant amount for a dam the size of the St. Francis, and on this subject Mulholland said, "Of all the dams I have built and of all the dams I have ever seen, it was the driest dam of its size I ever saw." The seepage data recorded during the 1926–1927 period shows that the dam was an exceptionally dry structure.

{snip}

On March 7, 1928, the reservoir was three inches below the spillway crest and Mulholland ordered that no more water be turned into the St. Francis Dam. Five days later, while conducting his morning rounds, Harnischfeger discovered a new leak in the west abutment. Concerned not only because other leaks had appeared in this same area in the past but more so that the muddy color of the runoff he observed could indicate the water was eroding the foundation of the dam, he immediately alerted Mulholland. After arriving, both Mulholland and Van Norman began inspecting the area of the leak. Van Norman found the source and by following the runoff, determined that the muddy appearance of the water was not from the leak itself but came from where the water contacted loose soil from a newly cut access road. The leak was discharging 2 to 3 cubic feet (15 to 22 US gal; 57 to 85 L) per second of water by their approximation. Mulholland and Van Norman's concern was heightened not only by the leak's location but by the inconsistent volume of the discharge, according to their testimony at the coroner's inquest. On two occasions as they watched, an acceleration or surging of the flow was noticed by both men. Mulholland felt that some corrective measures were needed, although this could be done at some time in the future.

For the next two hours Mulholland, Van Norman and Harnischfeger inspected the dam and various leaks and seepages, finding nothing out of the ordinary or of concern for a large dam. With both Mulholland and Van Norman convinced that the new leak was not dangerous and that the dam was safe, they returned to Los Angeles.

Collapse and flood wave

St. Francis Dam in February 1927

Two and a half minutes before midnight on March 12, 1928, the St. Francis Dam catastrophically failed.

There were no surviving eyewitnesses to the collapse, but at least five people passed the dam less than an hour before without noticing anything unusual. The last, Ace Hopewell, a carpenter at Powerhouse No. 1, rode his motorcycle past the dam about ten minutes before midnight. At the coroner's inquest, Hopewell testified he had passed Powerhouse No. 2 without seeing anything there or at the dam that caused him concern. He stated at approximately one and one-half miles (2.4 km) upstream he heard, above his motorcycle's engine noise, a rumbling much like the sound of "rocks rolling on the hill." Hopewell stopped, got off his motorcycle and smoked a cigarette while checking the hillsides. The rumbling had begun to fade, and Hopewell assumed the sound was a landslide common to the area. Hopewell finished his cigarette, got back on his motorcycle and left. He was the last person to see the St. Francis Dam intact and survive.

At both of the Bureau of Power and Light's receiving stations in Los Angeles and at the Bureau of Water Works and Supply at Powerhouse No. 1, there was a sharp voltage drop at 11:57:30 p.m. Simultaneously, a transformer at Southern California Edison's (SCE) Saugus substation exploded, a situation investigators later determined was caused by wires up the western hillside of San Francisquito Canyon about ninety feet above the dam's east abutment shorting.

The same view of the "Tombstone" post-collapse. The west (left) abutment was entirely swept away. The inactive San Francisquito Fault is clearly visible, being located along the contact zone of schist and conglomerate.

Power Plant 2 before dam collapse

Power Plant 2 after dam collapse

Given the known height of the flood wave, and the fact that within seventy minutes or less after the collapse the reservoir was virtually empty, the failure must have been sudden and complete. Seconds after it began, little of the dam remained standing, other than the center section and wing wall. The main dam, from west of the center section to the wing wall abutment atop the hillside, broke into several large pieces and numerous smaller pieces. All of these were washed downstream as 12.4 billion gallons (47 million m³) of water began surging down San Francisquito Canyon. The largest piece, weighing approximately 10,000 tons (9,000 metric tons) was found about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) below the dam site.

Somewhat similarly, the dam portion east of the center section had also broken into several larger and smaller pieces. Unlike the western side, most of these came to rest near the base of the standing section. The largest fragments fell across the lower portion of the standing section, coming to rest partially on its upstream face. Initially, the two remaining sections of the dam remained upright. As the reservoir lowered, water undercut the already undermined eastern portion, which twisted and fell backwards toward the eastern hillside, breaking into three sections.

Harnischfeger and his family were most likely among the first casualties caught in the initially 140 feet (43 m) high flood wave, which swept over their cottage about a one-quarter mile (400 m) downstream from the dam. The body of a woman who lived with the family was found fully clothed and wedged between two blocks of concrete near the base of the dam. This led to the suggestion she and Harnischfeger may have been inspecting the structure immediately before its failure. Neither the bodies of Harnischfeger nor his six-year-old son were found.

Five minutes after the collapse, the then 120-foot-high (37 m) flood wave had traveled one and one-half miles (2.4 km) at an average speed of 18 miles per hour (29 km/h), destroying Powerhouse No. 2 and taking the lives of 64 of the 67 workmen and their families who lived nearby. This cut power to much of Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. Power was quickly restored via tie-lines with SCE, but as the floodwater entered the Santa Clara riverbed it overflowed the river's banks, flooding parts of present-day Valencia and Newhall. At about 12:40 a.m. SCE's two main lines into the city were destroyed by the flooding, re-darkening the areas that had earlier lost power and spreading the outage to other areas served by SCE. Nonetheless, power to most of the areas not flooded was restored with power from SCE's Long Beach steam electric generating plant.

Near 1:00 a.m. the mass of water, then 55 ft (17 m) high,[54] followed the river bed west and demolished SCE's Saugus substation, cutting power to the entire Santa Clara River Valley and parts of Ventura and Oxnard. At least four miles of the state's main north–south highway was under water and the town of Castaic Junction was being washed away.

The flood entered the Santa Clarita River Valley at 12 mph (19 km/h). Approximately five miles downstream, near the Ventura–Los Angeles county line, a temporary construction camp SCE had set up for its 150-man crew on the flats of the riverbank was hit. In the confusion, SCE personnel had been unable to issue a warning and 84 workers perished. Shortly before 1:30 a.m., a Santa Clara River Valley telephone operator learned from the Pacific Long Distance Telephone Company that the St. Francis Dam had failed. She called a motorcycle officer with the State Motor Division, then began calling the homes of those in danger. The officer went door-to-door warning residents about the imminent flood. At the same time, a deputy sheriff drove up the valley, toward the flood, with his siren blaring, until he had to stop at Fillmore.

The flood heavily damaged the towns of Fillmore, Bardsdale and Santa Paula before emptying both victims and debris into the Pacific Ocean 54 miles (87 km) downstream south of Ventura, at what is now the West Montalvo Oil Field, around 5:30 a.m., at which point the wave was almost two miles (3 km) wide and still traveling at 6 mph (9.7 km/h).

Newspapers across the country carried accounts of the disaster. The front page of the Los Angeles Times ran four stories, including aerial photos of the collapsed dam and the ruins of Santa Paula. In a statement, Mulholland said, "I would not venture at this time to express a positive opinion as to the cause of the St. Francis Dam disaster... Mr. Van Norman and I arrived at the scene of the break around 2:30 a.m. this morning. We saw at once that the dam was completely out and that the torrential flood of water from the reservoir had left an appalling record of death and destruction in the valley below." Mulholland stated that it appeared that there had been major movement in the hills forming the western buttress of the dam, adding that three eminent geologists, Robert T. Hill, C. F. Tolman and D.W. Murphy, had been hired by the Board of Water and Power Commissioners to determine if this was the cause.

{snip}

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

0 replies, 462 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (0)

ReplyReply to this post