Strategies to Reduce the Environmental Lifetimes of Drinking Straws in the Coastal Ocean

The paper to which I'll briefly refer is this one: Strategies to Reduce the Environmental Lifetimes of Drinking Straws in the Coastal Ocean. Bryan D. James, Yanchen Sun, Mounir Izallalen, Sharmistha Mazumder, Steven T. Perri, Brian Edwards, Jos de Wit, Christopher M. Reddy, and Collin P. Ward ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2024 12 (6), 2404-2411.

I try to think about every piece of plastic I handle these days, considering that each may last centuries after my death. I avoid plastics where possible, but frankly it often isn't possible. In the case of straws, and for that matter cup covers, I avoid using them at all. You can drink liquids without a straw. I also have reusable coffee cups, two given to me as promotional trinkets by an instrument company trying to sell me instruments.

Anyway, straws are a problem:

From the introductory text:

An estimated 63–142 billion drinking straws are used in the United States annually, (1) contributing to the approximately $19 billion drinking straw market. (2) Complementary to their significant usage, drinking straws are a common, visibly jarring marine litter, accounting for approximately 5% of all shoreline and nearshore debris. (3) Because of this and their potential to harm charismatic megafauna, municipalities, states, and countries have begun restricting conventional polypropylene (PP) single-use straws in favor of those made from materials marketed as more degradable. Major brands have started adopting many of these bioplastic alternatives as they increasingly require the plastics they use to be biodegradable in all natural environments (e.g., compost, soil, freshwater, and marine). Yet, these regulatory and material selection decisions have lacked robust, environmentally relevant data to support them. The environmental lifetimes of single-use drinking straws and the biodegradation rates of their materials in the marine environment are uncertain. Unsubstantiated estimates for PP straws range from 100 to 700 years. (4) To date, the environmental lifetimes of commercial drinking straws in the coastal ocean are poorly characterized, and the controls on their environmental lifetimes are unknown, including the microbial communities that degrade them.

In this initial study, we aimed to constrain the environmental lifetimes of commercial drinking straws in the coastal ocean, determine the microbial communities assembling on and presumably degrading these items, and assess engineered strategies to minimize persistence. We exposed commercial drinking straws made of cellulose diacetate (CDA), polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), coated and uncoated paper, industrially compostable polylactic acid (PLA), and PP to marine microbes in a flow-through seawater mesocosm for 16 weeks. Throughout the experiment, we measured the mass loss of the straws and collected biofilms from the straws at the end of 16 weeks for microbial community analyses...

The authors passed seawater through straws of various composition, as described in the intro, photographed them and weighed them and studied the organisms growing on them.

Some graphical results:

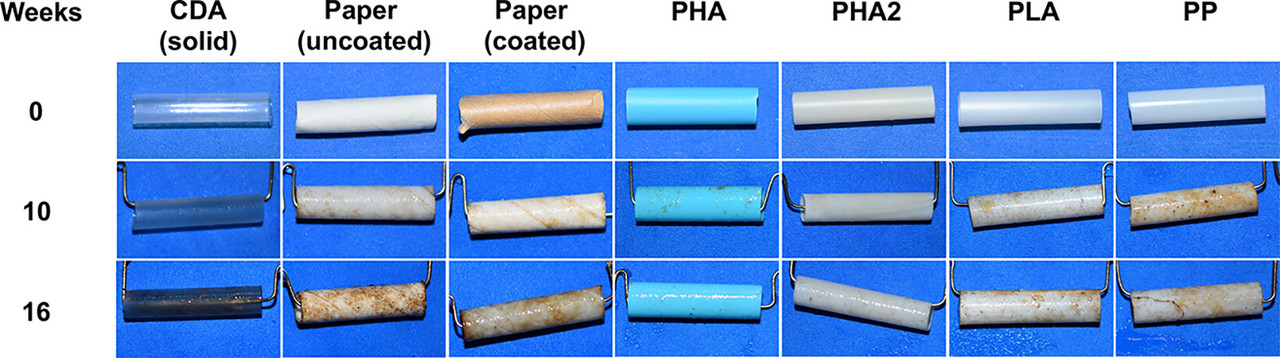

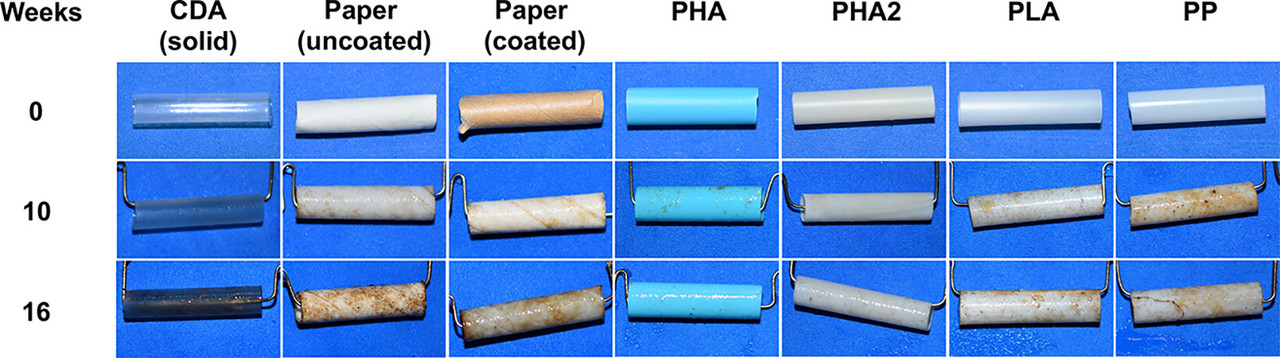

The caption:

Figure 1. Representative images of each straw initially and after 10 and 16 weeks in a flow-through seawater mesocosm.

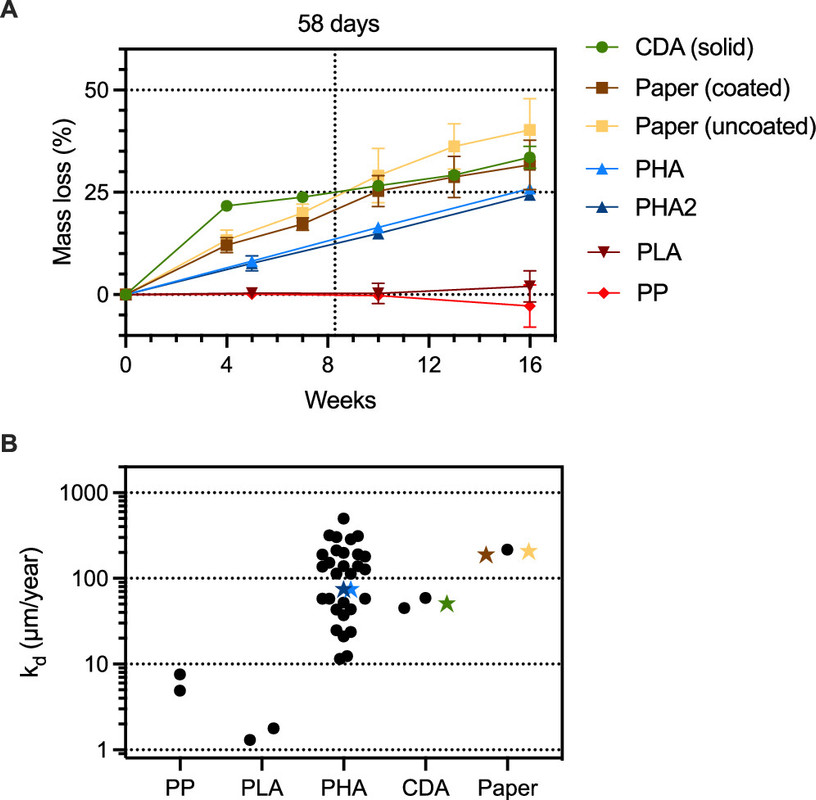

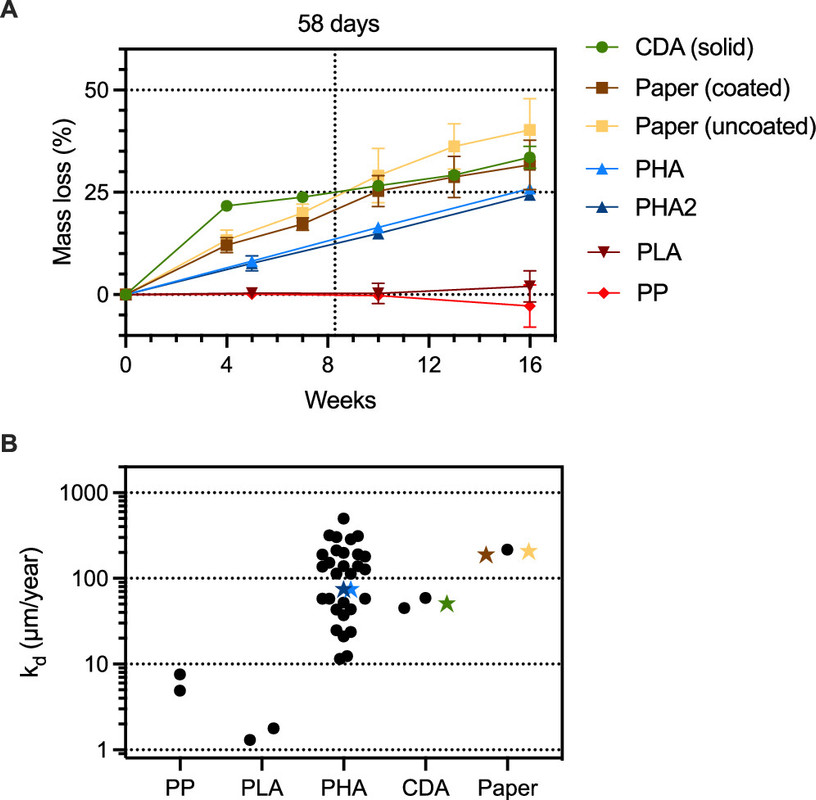

The caption:

Figure 2. (A) Relative mass loss of each straw (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3; Table S3). (B) Comparison of specific surface degradation rates (kd) measured for several plastic types and formulations in the marine environment; stars represent data from this study (Table S1), whereas circles represent data from the literature (7,22?32) (Table S4).

From the conclusion:

Despite the prevalence of drinking straws as marine debris, (3) their market capitalization is projected to grow by approximately $10 billion in the next decade. (2) In the face of this forecast growth, policies limiting or restricting the use of drinking straws or the materials for which they are made are becoming commonplace. Persistence is a key variable in regulatory frameworks; however, legislators lack robust, environmentally relevant data to inform decision-making. (4) Overall, replacement products must retain functionality while achieving sustainability goals, which has been challenging for paper straws cast as solutions to plastic straws. (38,39) Our study reports that many bioplastic straws are readily fouled and degraded by distinct microbial communities in the coastal ocean and, thus, are unlikely to persist and accumulate if leaked. Moreover, we demonstrate that seemingly simple engineering approaches (e.g., foaming) can substantially accelerate the degradation of readily biodegradable products, resulting in their reduced persistence. Future products should be designed for chemistry (using polymers susceptible to biodegradation), surface area (enhancing reactivity), and selection pressures (stimulating the growth of degrading microbes), thereby minimizing the persistence and, thus, ecosystem impacts of mismanaged plastics that leak into coastal environments.

Small things are big problems, and for the big problems we need people working on seemingly small things that turn out to not be all that small.

Have a nice evening.