Socialist Progressives

Showing Original Post only (View all)The Haymarket Affair -130 Years Ago Today [View all]

[CENTER][SIZE=4]The Haymarket Affair, or Why Most of the World celebrates International Workers' Day on May 1 and You Don't[/SIZE]

[IMG] [/IMG][/CENTER]

[/IMG][/CENTER]

May 1 is International Workers' Day, a commemoration in over eighty nations, but not the U.S.A., of the Haymarket Affair, whose themes persist today. The Haymarket Affair was the aftermath of an orderly, peaceful nationwide strike for safer working conditions on May 1, 1886. If you don't know about the Haymarket Affair, that is no accident: "No single event has influenced the history of labor in Illinois, the United States, and even the world, more than the Chicago Haymarket Affair. It began with a rally on May 4, 1886. Although the rally is included in American history textbooks, very few present the event accurately or point out its significance....."

Actually, the story of the Haymarket Affair began shortly after the Civil War, when industrial production began growing rapidly. American laborers worked for very low wages, ten to sixteen hours a day, six days a week, often in dangerous conditions, causing avoidable deaths and injuries. Hence, a labor movement for safer working conditions, including an eight-hour work day, began in the 1860s. After the Depression of 1873–79, industrial growth accelerated. During the economic slowdown between 1882 and 1886, socialist and anarchist organizations became active, including within the labor movement, much to the consternation of the establishment. In Chicago, tens of thousands of German and Bohemian immigrants were working for about $1.50 a day, making Chicago a hub of labor activism. Employers responded with union-busting measures, such as firing and blacklisting union members, lockouts, hiring non-union workers to replace strikers ("scabs"![]() , exacerbating ethnic tensions in order to divide the workers from each other and hiring spies, thugs, and private security forces (notably Pinkerton). (Divide et Impera is older than dirt, yet we still fall for it.) Mainstream newspapers supported business interests, as does mainstream media now, while activist, often immigrant, press supported workers and unions.

, exacerbating ethnic tensions in order to divide the workers from each other and hiring spies, thugs, and private security forces (notably Pinkerton). (Divide et Impera is older than dirt, yet we still fall for it.) Mainstream newspapers supported business interests, as does mainstream media now, while activist, often immigrant, press supported workers and unions.

In 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions in both the United States and Canada set May 1, 1886 as a deadline for passing laws to limit a work day to eight-hours. Labor organizations prepared for a general strike on that date, as did police and militias. The strike was very well-planned. On Saturday, May 1, 1886 (then a work day), 300,000 to 500,000 workers across the United States struck, rallied, demonstrated and marched peacefully, with the cry, "Eight-hour day with no cut in pay," with perhaps twice their number joining them on the streets. Chicago saw by far the largest group of strikers (40,000 to 90,000) of any city. August Spies, who ran Arbeiter-Zeitung ("Worker's Newspaper"![]() , a German-language activist newspaper, led strikers in a parade up Michigan Avenue.

, a German-language activist newspaper, led strikers in a parade up Michigan Avenue.

On Monday, May 3, the next workday, over 65,000 rallied in Chicago, some near the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. McCormick's union molders had been locked out since early February. A garrison of four hundred police officers were protecting the scabs McCormick had hired to work in place of union members. (During a strike the year before, Pinkerton guards had attacked the predominantly Irish-American work force.) About half the scabs had defected to the general strike on May 1. McCormick's union workers were heckling the scabs who were still crossing picket lines to work at the plant. A few miles from McCormick's, Spies was addressing members of the the Lumber Shovers' Union. After some of his audience broke away to join the workers outside McCormick's, Spies heard shots. He and some of his listeners went to McCormick's, where Spies spoke, urging union solidarity. When the end-of-the-workday bell sounded, a group of workers surged to the gates to confront the scabs. Although Spies appealed for calm, police fired, killing either two or six McCormick union employees, depending upon the account. Spies later testified, "I was very indignant. I knew from experience of the past that this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement."

That evening, several anarchist leaders met and called for a meeting/rally the next evening (May 4) to protest police violence at McCormick's. Meanwhile, Spies had gone to the offices of Arbeiter-Zeitung to write about the day's events. His report, which would appear in Arbeiter-Zeitung on May 4, the day of the Haymarket rally, claimed that two hundred police had fired on fleeing workmen and women. "They pretend subsequently that they shot over their heads. But be that as it may, a few of the strikers had little snappers of revolvers, and with these returned the fire. In the meantime other detachments had arrived, and the whole band of murderers (police) now opened fire on the little company - 20,000, as estimated by the police organ, The Herald, while the whole assembly (of strikers and their allies) scarcely numbered 8,000." Spies' report also stated that Cyrus McCormick, owner of the Reaper Works, had commented, "August Spies made a speech to a few thousand anarchists. It occurred to one of these 'brilliant heads' to frighten our men away. He put himself at the head of a crowd, which then made an attack upon our Works. Our workmen fled; and, in the meantime, the police came and sent a lot of anarchists away with bleeding heads," referring to police beating workers' heads with billy clubs. Spies entitled his report Workingmen to Arms!, which was published the next day under his title, Blood, and distributed as a broadside. However, without Spies' knowledge, the typesetter added the additional title, "REVENGE!"

[CENTER] [IMG] [/IMG] [IMG]

[/IMG] [IMG] [/IMG][/CENTER]

[/IMG][/CENTER]

At the Haymarket rally on the evening of May 4, 1886, Spies was the first speaker. The second was Albert Parsons, whom Spies had recruited to speak at the last minute. Parsons addressed the crowd for nearly an hour, then left. The third and last speaker was Samuel Fielden, who spoke only ten minutes. By this time, most of the crowd had left. At about 10:30 p.m., as Fielden was finishing, police marched in formation toward him and ordered the rally to disperse. Fielden protested that the meeting was peaceful. Police Inspector John Bonfield responded, "I command you (Fielden) in the name of the law to desist and you (the crowd) to disperse." Someone threw a bomb in the path of the police. A mêlée, in which police and demonstrators shot at each other, ensued. A total of ten policemen and at least four workers died, with scores injured.

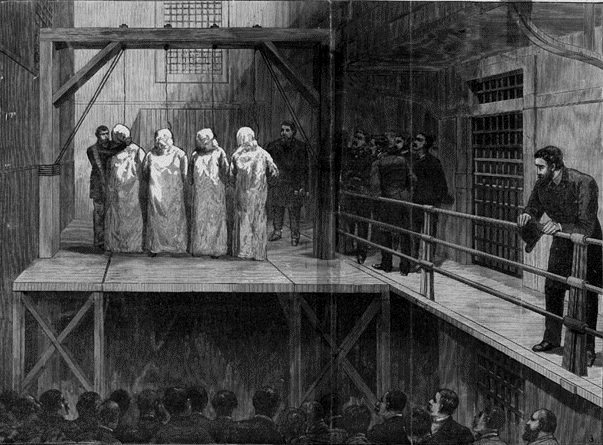

Eight anarchists were tried for murder: Fielden, Parson and Spies (the three speakers at the rally), George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe and Michael Schwab. Of the eight, Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg and Schwab had been born in Germany; Fielden had been born in England; Neebe had been born in the U.S.of German descent; and Parsons had been born in the U.S. of British descent. Despite weak evidence and questionable practices, all eight were convicted. All but Neebe were sentenced to death, with Neebe being sentenced to fifteen years in prison. After appeals (with the Supreme Court of the United States denying certiorari), executions were scheduled for November 11, 1887. The day before, Governor Richard James Oglesby commuted the sentences of Fielden and Schwab to life in prison and Lingg committed suicide by using his teeth to detonate an explosive cap, dying after an agonizing six hours. The next day, Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies were hooded, robed and taken to the gallows, where they sang the Marseillaise, then the anthem of the international revolutionary movement, before they were hung. (They strangled to death slowly.) In 1893, Governor Peter A. Altgeld pardoned Fielden, Schwab and Neebe, an act that may have cost him his political career. In the above image, Spies is in the center, Fielden at the top, then, clockwise, Lingg, Fischer, Engel (bottom), Schwab and Parsons.

The incident was the first great “red scare” in American history. Although many in the labor movement view the men who had been convicted as martyrs, the Haymarket Affair was then viewed as a--wait for it--setback for organized labor in the U.S.A. (not for the First Amendment and other provisions of the Bill of Rights, not for the judicial system, not for law enforcement, not for mainstream newspapers and not for worker-exploiting, union busting employers!). The Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor lobbied for a national holiday. Enter President Grover Cleveland (who happened to love him some strike-breaking). Cleveland feared that Labor Day would become an opportunity to commemorate the Haymarket Affair. Thus, in 1887, he established Labor Day as an official holiday to honor the American labor movement and the contributions that workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of their country--but he scheduled Labor Day for the first Monday in September, not May 1. Nonetheless, for years, U.S. workers continued May 1 observances and commemorations of workers and labor leaders who had died as a result of the fateful events of May 3 and 4, 1886.

In 1970, the AFL-CIO declared April 28 “Workers' Memorial Day,” to honor those killed, injured, disabled or otherwise made unwell because of their actual jobs and that is wonderful. However, I believe strongly that we in the U.S.A. should join in solidarity with most of the rest of the world in honoring, on every May 1, the martyrs of the Haymarket Affair and all others who fought, before and after 1886, for a right to unionize and for safe, humane working conditions, including the eight-hour work day.

[CENTER][IMG] [/IMG]

[/IMG]

May 1, 1909 Labor Parade, Manhattan

[IMG] [/IMG]

[/IMG]

May 1, 1913 Labor Strike, Union Square, Manhattan[/CENTER]

[CENTER][video=youtube;pCnEAH5wCzo]

Sources:

[url]http://www.democraticunderground.com/11177664[/url] (Evolution of Labor Day, a great thread in Omaha Steve's Labor Group, by Omaha Steve, aka JPR's Wizard of Os, himself.)

[url]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_Day[/url]

[url]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Workers'_Day[/url]

[url]https://blogs.shu.edu/history/2015/10/17/does-wikipedia-tell-the-truth/[/url]

[url]http://www.history.com/topics/haymarket-riot[/url]

[url]http://www.iww.org/history/library/misc/origins_of_mayday[/url]

[url]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grover_Cleveland[/url]

[url]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labor_Day[/url] (The entire article is well worth reading.)

[url]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbeiter-Zeitung_%28Chicago%29[/url]

[url]http://www.lcweb.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/connections/haymarket/history4.html[/url]

[url]http://www.massaflcio.org/1886-general-strike-8-hour-day[/url]

[url]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workers'_Memorial_Day[/url]

[url]http://aattp.org/read-the-real-bloody-and-amazing-story-of-labor-day/[/url]

[url]http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/haymarket/haymarketdefendants.html#engel[/url]